Anton Furst

From the fantastical Gotham City in Batman, to Vietnam War-scapes in England in Full Metal Jacket, Furst’s imagination and technical brilliance played an indispensable role in ushering in a new era of production design.

April 1, 1990

A native of Britain, Anton Furst was on his way to medical school when he realized that the one thing he could do better than anyone he knew was to draw. Consequently, he chose to apply to the Royal College of Art, which happened to be next door to the Imperial College of Sciences. This arrangement made the possibility of combining his dual interests—art and science—completely accessible; besides studying illustration, he was able to create three-dimensional images using optics and lasers. After earning his degree and two traveling scholarships to America, first with the Czech stage designer, Josef Suoboda, and then with designer, Charles Eames. When Furst returned to London he took a job with one of his heros, Tony Masters, the production designer of 2001. His next project, a show of holography at the Royal College, was nearly aborted when the main “tube blue” blew—it would have cost the department’s entire budget to replace. Instead, the resourceful artist had an inspiration. It was 1977 and The Who were using lasers in their stage show. On a whim, Furst rang them up.

“I happened to get Daltry who said ‘Just a minute, mate, I’m finishing up lunch. I’ll ring you back’,” explains Furst, doing a smashing imitation of a working-class accent. Dressed in jeans and a leather jacket, he’s leaning back on a couch in an office on the set of Awakenings, the film adaptation of Oliver Sacks’s book, directed by Penny Marshall, and starring Robert DeNiro and Robin Williams. With his dark good looks and animated delivery, he could be a visiting actor. He is, in fact, the production designer. His office is by far the most colorful on a set occupying three floors of a working State Hospital in Brooklyn. “So I went back to the lab fairly depressed,” he continues, "thinking, probably not. And within a half an hour he had a fuckin’ helicopter turning up on the lawn with three lasers and three technicians in tow. I was pinned to the wall by Daltry, barking, ’Who’s involved in this thing?’ " The Who took over, donating space and money, and the result was “Light Fantastic,” a “hugely successful laser show that attracted football size crowds and was bigger than punk at the time.” After another blockbuster the following year, the same producers, including the faculty, Furst, and the band, with additional financing from Agfa, built the biggest special effects lab in England, based at Shepperton Studios. This was the era of the special effects movie—Star Wars, Alien, The Empire Strikes Back—and, as the artistic director of the company, Furst found himself spending more and more time overseeing the staff and the business. “I was the front man of the operation and I wasn’t really doing my art,” he says, lighting up a pipe. It’s late on a December afternoon, midway through a lengthy shoot. This may be the first time he’s put his feet up since the six a.m. call that morning. “I was producing creative things, but I felt if I wasn’t at the drawing board, I was really only servicing other people’s whims—someone else was designing them.” Four years on, he took a leave of absence from Shepperton to design a two and a half hour TV movie and never went back. His next call was from director, Neil Jordan.

Needless to say, the company’s loss was the film world’s gain. Furst went from designing The Company of Wolves to Full Metal Jacket to High Spirits to 1989’s Batman, for which he will probably win an Academy Award.

Lynn Geller Your first feature was Company of Wolves, I remember it looked almost like a dream.

Anton Furst It’s a pubescent girl’s dreams and fantasies told by a cautionary aunt played by Angela Landsbury. It was designed like a fairy story—little villages in the woods. We did it all in the studio, even the exteriors. We were trying to develop something which was the fantasy of a child, a dreamworld with its own reality. We had very complex forced perspectives, what we call dioramas so that you had specific views. Can you remember the little village down there and the church up on the hill? It was different from anything else coming out at that period. It needed a magical feeling about it because it was magic. Remember the wolf coming out of the guy’s mouth? I always regard Neil’s scripts as a form of poetry. Anyway, Kubrick saw it and said, “Get a hold of that guy, he’s our designer.” On Christmas day he rang me up and said, “I want to send you my script, it’s gonna be a great script.” It was Full Metal Jacket. He wanted to do it all in England—the Vietnam War in England. I looked at the script and thought, What?, and said, “Yes.” Although his reputation does precede him. You know the implication in the film industry—if you do a film with Kubrick and survive it—two years that was, it tends to put you at the top of the shit heap. If you can handle it with Kubrick then they think you can handle anything because he’s 44 times more difficult than anybody else.

LG I heard an amazing story about him hearing a fly on the set. I was going to do a book with a friend of mine about location shooting—Kubrick, who invents his own locations, versus the ultimate in being on location, Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Kubrick’s are the most controlled circumstances possible.

AF You have to get through three electric gates to get to him. At the last gate, you get into an armored car which he sends down from his mansion.

LG No, no. Does he have agoraphobia?

AF Yes, yes. He hates making movies cause he’s got to go out of his house. I’d say it’s similar to Howard Hughes. Megalomania. He’s intensely shy and awkward, increasingly so. He works with the smallest crews. In real terms, I’d say he only talks with myself and Dougie Milson—the lighting and camera man, the director of photography—and then through us to other people. I had a very big department, we had a port-a-cabin village built. He walked into a 50-foot room with 14 drafting guys and me at the end and I saw him just go—like that. He walked out of the port-a-cabin without saying a word. Rung me up from outside on his car phone and said, “I just want you to come out and meet me in the car for a minute, you’ve got to get your own office. We’ll have another port-a-cabin brought down. I cannot, I cannot talk in there.” He’s like that. He has to be in an intense, small unit and then he’s happy. That’s why he spends a lot of time in his Winnebago with televisions and only comes out on the set when he has to and he’s got cages built . . .

LG What if a regular guy had that problem? What would he do as a profession? He’s so lucky. Well, maybe not lucky . . .

AF He is lucky because he has a wonderful home life. He adores his wife and family and he loves his dogs and cats and all that is lovely. I’m not sorry for him because he can actually enjoy the way he wants to live his life. He only has to make a movie every six years—in his case. The worst aspect is the couple of months before shooting when he realizes that in eight weeks time he’s going to have to go out…so he starts causing problems, anything so that he can put it back. He’ll start disliking everything you do so that he can actually hold it up. Once we were shooting, it all got easier. Then he had to concentrate on a hundred crew members, and not just me. I must tell you, though, that I have enormous respect for him. He’s a formidable intellect, a huge mind—prodigiously bright—if the word genius applies to anybody, there’s an element of that in him. I think he’s the best lighting and camera man in the world. I was mind-blown when he first called me. It becomes a campaign, making a movie with him, a war-campaign where strong bonds are made with people who come through to the other side of it. Afterwards, whenever you meet, you’re very close. Most people get fired at some point on the picture, in the course of two years. Stanley and I definitely got on and I think there are a few tricks that I learned pretty quick with Kubrick. If you know that you made a mistake and go to Stanley and you say, I think I fucked up and I’m going to have to redo, he couldn’t be an easier director to work for. If he comes down and you haven’t told him, you’ve tried to cover it up, you’re fired. He’ll be cruel, absolutely appalling, and he’ll never trust you again. Even if you try to cover for someone else, he’ll immediately suss it out. He grasps everything. You can’t bullshit him. You can’t. Bottom line. I like Stanley and I admire him.

LG You weren’t trying to re-create Vietnam with Full Metal Jacket were you?

AF Not exactly. We saw about 6,000 photographs of the Vietnam War. We took what we thought were the most powerful images with the most impact. For instance, when the squad went into the burned out city of Quai, we had every building on fire. That was probably an exaggeration. We had seen some shots where it looked like everything was on fire. We weren’t going for complete historical accuracy. So we built sculptural images and lit that whole section of the film with available light and fire. We didn’t want blue skies. If the sun came out, Stanley didn’t shoot. It was supposed to be the image of hell.

Set for Full Metal Jacket.

LG Wasn’t the perspective in the beginning of Full Metal Jacket really exaggerated?

AF Yes and repetitive, repetitive images of men on racks that went on and on. It was actually almost true of the boot camp, Paris Island, at the time, though we shot it in an augmented way to drive the point home. Paris Island was supposed to train them for their tour of Vietnam. So we contrasted the unbelievable cleanness, spic and span quality of the boot camp with the incredible filth, the shit, of the actual war. The point was that they came up against something they could never have trained for. All of Kubrick’s films are about the frailty of the human condition in extreme circumstances, from Clockwork Orange to Paths of Glory to Full Metal Jacket. We went for the power of the imagery. I don’t like to look too hard at references. I just look enough to know where to go from and how far I can go. Otherwise, you get hung up on detail. It’s much better to go for the broad stroke. With Gotham City for Batman, for instance, I’d been to New York before, but they asked me if I wanted to go back to do research and take photographs. I said, “No.” I knew enough about New York and its architecture, the tone and the feeling and that’s all I wanted to know. I changed the reality to give it a different perspective. I work on metaphors and parables of situations. Gotham City is all the elements of Manhattan exaggerated. You can tip it one way or another, and five percent more one way, it’s unbearable. Any New Yorker is aware of that five percent balance, where the place could just fuck up on a moment’s notice. Con Ed ripping up the pavement or a lorry creating gridlock for miles. I imagined what it would have been like if it had been run by a criminal organization for a long time and had been allowed to become what you saw in the film.

LG With a Good vs. Evil scenario, you have to avoid getting too pedestrian.

AF Yes, and once you’ve gotten into this almost abstract situation with the city and car, then the characters can be entirely unique. The Joker can go crazy, Batman can put his cape on and you can set up a whole integrity for the movie. They’re basically just a couple of psychotics; one dresses up as a bat at night and the other runs around in whiteface with green hair. We had to turn the whole film into this extraordinary fantasyland of its own to let these things occur.

LG Besides the hype, what do you think it was about Batman that so captured the audience and made it such a phenomenon?

AF I think what the producer, Jon Peters, would say, is that there were certain inconsistencies and weaknesses in the story and script, but indigenously, this wonderful visual landscape held the whole thing together. One of the things that all of the films we’ve spoken about offer is the power of the image. What Peters said is that the design of Batman became as much of a personality as Michael Keaton or Kim Bassinger. It became a character. I may have taken design into that new area just a little bit. Because it’s cinema, if you take the imagery to a certain level, it can be as important as any other aspect of the film. Not in all films, of course. Certainly, in Awakenings, DeNiro and Williams are more important. This film lives or dies on the success of their performances, the direction and the script. The bottom line is always the script. But there are certain movies that require a whole reality, a world and in those, the design and visual aspect becomes as significant as any other element. So with Batman, the producers realized that people were going to see the Batmobile and Gotham City in the same way that they saw, for instance, the Yellow Brick Road in the Wizard of Oz. In Awakenings, it’s a question of me supporting humor or wit with a relatively light area to the space, a light, simple void rather than keeping it down and dark and gloomy as Batman.

Drawing for The Company of Wolves.

LG How does that approach translate when you’re doing a movie like Awakenings, which is reality-based?

AF On this film, I’m constructing something which is spiritually right in order for the script to tell the story. I’m not taking references from hospitals or anything like that. I’m trying to re-imagine the situation and to open it up, give it some lightness, so that the audience can cope with what is an exceedingly heavy story. I haven’t gone for literal things. Again, I’ve gone for a heightened reality. I’ve simplified the backgrounds, so you’re always looking at the actors and can really concentrate on them. In the same way I starved Gotham City of color to exaggerate the Joker’s look. The same way that Batman is always coming out of the shadows and disappearing and re-appearing. You never quite see him properly. In the case of Awakenings, I’m trying to take an element of Diane Arbus, putting these characters in an uncomplicated background, almost in a void, isolating them. Instead of putting people into little boxes, which would have been too claustrophobic, we put the patients into a big, spatial void. So again, I’ve taken a fairly abstract approach. To make it gloomy would be to make it almost intolerable for a mass audience. It’s a $32 million picture. You’ve got to draw in the audience to be able to tell the story. I suspect that’s why Penny Marshall wanted me to do the film, because she knew it couldn’t be done literally and that she’d have to find the right context and tone, in order to find the humanity and the slightly more humorous aspects.

LG Awakenings is being shot in New York?

AF This film is starting at 17 weeks and I say it’s going to go to 20, 23. That’s a very long shoot.

LG Now when did this start?

AF Early October.

LG But you’ve been working on it longer than that, right?

AF Oh, yeah, since August. What I’m trying to say, is I’m not trying to recreate the absolute reality of a hospital. I’m trying to develop a context for the film which will be spiritually correct or tonally correct. I don’t agree with the idea of trying to reconstruct a reference shot of something from some period. I believe in looking at the film and then thinking in the abstract. And then reconstructing your own reality to support that general abstract idea of the whole piece.

LG What sort of research do you do?

AF You look at the implications—the script immediately suggests certain references which lead you to others and you think, Yes. But you are always trying to achieve something spiritually and tonally so you look at references in that area. Then you begin to roll. You always try to think artistically about composing shots.

LG Are you working with the DP or the Director?

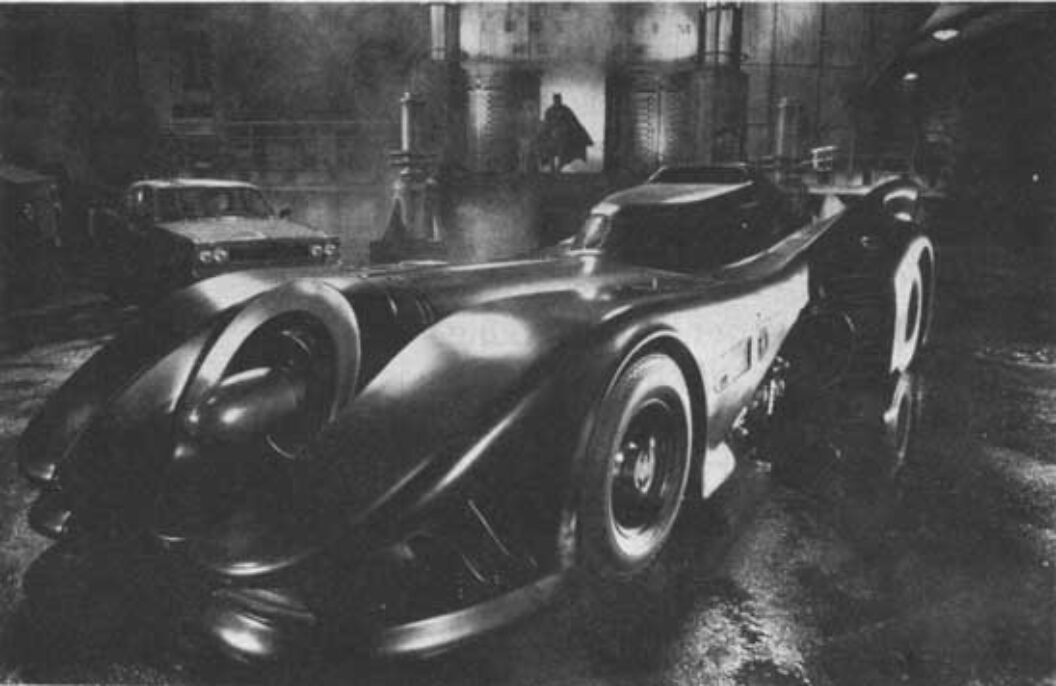

AF The Director. The DP tends to arrive pretty late on a picture, a few weeks before you shoot. Things are discussed and adjustments may well be made. If you’re good at it, you design your sets with a lot of flexibility for different lighting possibilities. Batman is the best example [and Company of Wolves because that was the kind of theatrical design and filmmaking that had its own integrity. You’re designing visual drama. Even the car. The Batmobile was more like a knight in armor, an extension, an expression of Batman’s costume—an intimidating, furious war machine. We didn’t spend much time looking at concept cars of the future. We went back in time. Tim Burton and I inevitably got together because he is firm in his opinion that film must have it’s own reality. The more you explain the more you have to explain. If you start explaining you have to explain loads and that gets off the event you’re actually reconstructing. Look at a Disney cartoon. Everybody buys that Donald Duck was steamrolled flat. Once it develops its own indigenous reality, who’s interested anymore in Jean-Luc Godard’s Cinema Verite? Taking a camera into real life, putting actors into it and shooting that? It was a big deal in the ‘60s and the ‘70s. I am not an exponent of Cinema Verite. That’s not what you can do with cinema. Full Metal Jacket describes a specific situation. But we augmented that to describe the actual situation more clearly. You’ve go to do it in an hour and a half, two hours. The strength of your graphic imagery is incredibly important. You must really ram it home hard and fast ‘cause you ain’t got time to go to it like in a book. It’s a two hour job, it ain’t a couple of days. You’ve got to really take ‘em in. But it has to be honest to the feel of the thing. Kubrick never takes film and says, I’m producing reality. He says I’m producing a movie which will describe the point I’m trying to fucking well make with everything I’ve got, visually, dramatically, cinematically, and graphically to get through major points—the frailty of the human condition or whatever. It’s purely an event.

The Batmobile.

LG When it comes down to designing an entire room, like the operating room in Awakenings, where the audience knows how the instruments are supposed to look . . .

AF I do drawings of things as a broad stroke scheme, I do actually go into quite a lot of detail on those drawings, because it’s suggestive. I project a perspective up on a 25mm lens so that a wide lens shot will be covered. No one wants to build more than they need. Going up the big Gotham Cathedral, we had to work extremely complex camera angles and draw it up. There’s a method, you project a layout up into elevated perspective 45 degrees through to 90 degrees and when you get it up there, take your measurements. I draw into that so I know what we’re going to look at in that shot. You’ve got to break it down into all the elements you need. I picture the batwings swinging round the Cathedral, going down the street, and think that street’s going to be the model street that we’re using. The foreground will be a foreground model of the Cathedral put in a different scale so it flashes forward and the background will be a matte painting from their eye-range. So you have to do axiomatic projections of the rest of the city beyond that and then you can shoot the batwing motion control in front of a blue screen and then matte that in afterwards, going around the Cathedral and down the street. You list underneath that one shot, all the elements you’re going to have to shoot and from what angles to make that one shot of four seconds. On a complex effects film like that, you have to literally storyboard the whole film shot by shot.

LG You don’t have a whole lot of special effects in Awakenings?

AF Maybe two matte shots. It is normal, straightforward filmmaking. Are you asking me why I’m doing this film? When I was in Hollywood at the opening of Batman, I had about 14 scripts to look through. And, quite honestly, I looked at this script and thought all the rest were second-rate compared with it. Penny Marshall came actually to the Batman opening and said to Tim, “I want Anton to design the interior, a mental institution.” He just laughed out loud. I went out to see Penny at her house in Hollywood, and said, “Seriously, you’ve just seen what I do, why are you asking me to do this?” And she said, “Why not? Why not? Is there something I should know? Have you got a problem? Do you have a sort of character defect that I don’t know about? I want it to look right. I want a world-class camera man…” Anyway I thought it was a great script. And to be absolutely honest, New York is something which can sustain you for six months of being on location. I hate location movies in the middle of nowhere, they send me crazy. It all sounds great, I’m going to the Seychelles for six months and after three weeks, you think, Four and a half months of this fucking place and I’ve already been to every restaurant? New York is great. It worked in well timing-wise, because I’m taking stock at the moment of precisely how I’m about to move forward. A lot of things were happening after Batman.

Jack Nicholson in Batman.

LG You must be besieged.

AF I wasn’t here; I was in L.A., and I was glad to be out of England when Batman opened there. I couldn’t go through all the same things again. Yes, it was big from my point of view, that film. Awakenings is being regarded with enthusiasm. There’s a general feeling that it’s going well.

LG It’s a good quality . . .

AF Whether it will make money or not I can’t tell but it has the spirit, I think Penny will make sure of that, and Robin as well. It’s a depressing, heavy story, but then, Cuckoo’s Nest was, too. Fucking lobotomy, the guy goes crazy, smashes the window and runs away. I mean terribly tragic, but there’s a spirit in the movie that was very successful, wasn’t it?

LG It’s really not predictable. They keep trying to make it predictable. They take surveys and do all this marketing, everything they possibly can to make it predictable and in the end, something comes out of left field, and that’s the big hit. How do you feel about American versus English movies, or do you care?

AF I haven’t worked for England for six years. I’ve been working in a manufacturing system for Hollywood on the films they decided to do at Pinewood or Shepperton because it’s more convenient to do it in England, or cheaper or better. Largely due to 2001 being made in England twenty years ago, many new systems and the highest standards of techniques were worked out. 14 new processes of special effects were invented on that picture. That legacy paid off. That’s why Star Wars came to England. So I have literally been working for Hollywood in England.

LG You have to assume that fairly international lifestyle. It’s a very modern way to live.

AF England is not the be all and end all. I happen to have been brought up and educated there, but I’m not English. My father’s Russian, my mother’s French. I like it, but I don’t like Thatcher’s England. You can record that. She’s killed the culture of the country dead. It’s much more interesting here right now.

LG Although politically . . .

AF What, here? Well, it’s not great here either. But at least there’s an appetite here. She’s managed to kill that for England. She’s given the city and the yuppies the money and dissipated the industries at every single level. The culture hasn’t been developed and now it’s really showing.

LG What kind of movies do you enjoy? I mean, what movies have an impact on you?

AF That’s a pretty tricky one, I have to cover the waterfront a little. In the end, it’s the movies with integrity of their own. It’s seldom that you see a little gem of a film, or big gem of a film, that’s got absolute integrity from front to back. The Last Emperor had integrity from front to back, in its stylistic approach. It was cinematographic, had wonderful acting and sustained three and a half hours of pure integrity. I like people who use the actual art-form of cinema: Kubrick, Fellini, Bertolucci, Tim Burton. It’s like, come and have a look at this event.

Furst drawing for the chemical factory in Gotham City.

LG Come, and enter my world.

AF Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander is a masterpiece. I liked Radio Days. All films that use cinema as the way of fundamentally expressing the points they’re trying to make, rather than then expressing a literary piece on film.

LG So let’s say, Sex, Lies, and Videotape?

AF Great. I thought it was great actually. The relationships were brilliantly manipulated and it was very clever. And boy, what a bird!

LG Which one?

AF Umm, the one that, the other one. She’s apparently very hot now in Hollywood. It’s like . . . they’re both amazing, but she’s got something which is unusual, there aren’t many around like her. The one who’s not beautiful but she’s got something. Like, here I am, fuck me. Indefinable really, isn’t it?

LG . . . openness, complete total openness.

AF There’s not many really, who have that kind of sexuality. Since the ‘60s, the whole Twiggy thing of everybody becoming thinner and thinner and thinner and thinner. Until you’re nothing. And that ain’t Marilyn Monroe. Ask any man which they prefer. It’s beginning to crack.

LG Well, yeah, Kim Bassinger.

AF Kim and Melanie Griffith and this girl. The Women’s Movement is probably the most significant movement of this century, but various elements of that got caught up in the-don’t-take-me-for-a-sex-object.

LG Who wants to be a man? I happen to think that men and women are different. All you have to do is be around little kids.

AF It’s a tragedy when you break that down. Equal rights, equal opportunity, equal everything, but let them wear a skirt or let them be women. Women do want everything men can have, which is dead right.

LG Yeah, they just don’t want to be men.