A Profile of Fletcher Hanks

by Joshua LH Burnett

The 1940s were a unique time for comics. Superman was only a few years old, while Fredric Wertham and the subsequent Comics Code Authority were still a decade away. In this Golden Age, the very concept of what a superhero was and what superhero stories were about was still forming, nebulous and unpredictable, from chaotic clay. America’s youth had a nigh-insatiable hunger for comics, and the myriad publishers hired artists and writers with wildly varying tastes, styles, and levels of talent. It was only in this primordial time of comics that Fletcher Hanks could have made his name—several names, in fact.

Fletcher Hanks was born in 1887 and raised in Oxford, MA by Rev. William and Alice Hanks. According to family, young Hanks was a spoiled and indulged child who grew to be a troublemaker and bully. When he was 23, his mother paid for him to take the W. L. Evans correspondence course in cartooning. Surviving drawings and assignments from Hanks’ coursework shows that the budding cartoonist had a solid understanding of anatomy and technical skill, despite the later comics he would become known for.

Hanks married and had four children—William, Fletcher Jr., Alma, and Douglas. Sadly, he had grown to be a violent and abusive alcoholic. He made money painting murals for wealthy clients, then spent all his earnings on booze. In 1930 he stole all the money from Fletcher Jr.’s piggy bank and left his wife and children for good. They were glad to be rid of him.

In 1939, Hanks started his two-year career as a cartoonist. He produced work for the Eisner & Iger agency, founded by comics legends Will Eisner and Jerry Iger. Eisner & Iger was a comic book “packager” that produced on-demand comic stories for a variety of publishers. Hanks was unique among the artists at Eisner & Iger. For one, he was more than 30 years older than most of his coworkers. Hanks was also unusual in that he wrote, penciled, inked, and lettered all his work himself, rather than split the work among multiple people. Hanks used numerous aliases for his work: Barclay Flagg, Bob Jordan, Charles Netcher, and Hank Christy. Only his “Stardust” stories were published as “Fletcher Hanks.”

Hanks’ comic art showed a marked change from the more technically precise work of his youth. His characters displayed bizarre aberrations of anatomy and posture. Many of his creations featured compellingly grotesque qualities like the work of Basil Wolverton. His gangsters sport jutting brows and twisted lips. Eyes bulge and musculature defies standard physiology.

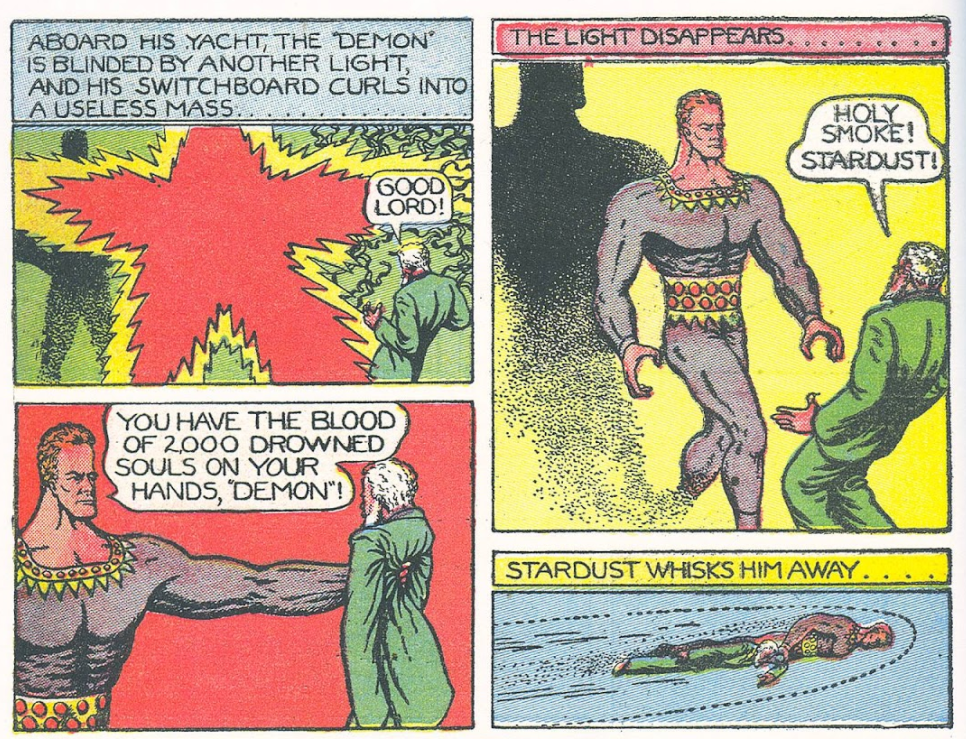

His stories were as bizarre as his art. Certainly heroes like Superman and the Phantom would throw fists to punish criminals, but Hanks, a bully himself, created stories centered around violent retribution. His comics focused on creative brutality rather than any greater social concerns. Where Superman might punch a bank robber and deliver him to the police, Stardust the Super Wizard would crush the saboteur’s body with giant fists and throw him into orbit around the sun.

Fletcher Hanks created many characters over the two years he worked in comics. Stardust and Fantomah are his most famous. Stardust the Super Wizard lives on his own “private star” where he monitors Earth for crime. When trouble arises he flies to Earth in his “tubular spacial” or suddenly appears in a fiery burst of light and thunder like an Old Testament God. He metes out violent justice using his fearsome strength and his mastery of “scientific rays.”

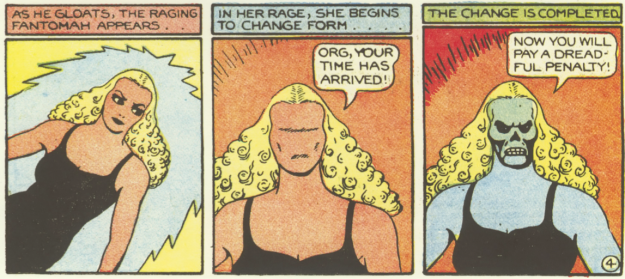

Fantomah has the distinction of being the first female superhero. The “Jungle Goddess” normally appears as a scantily clad blonde woman, but when poachers or mad scientists threaten the jungle, her face turns into that of a leering skull. In this form she swoops down from above to brutally kill the offenders.

Hanks created many other, less-popular characters. Space Smith is an adventurer in the mold of Flash Gordon, who flies across the galaxy with his girlfriend Dianna, punching various alien overlords. Big Red McClane is a burly lumberjack who fights corrupt gangs. Tiger Heart is a Prince Valiant type of warrior-noble who lives on a Saturn that looks mysteriously like medieval England. Yank Wilson is a super-spy who thwarts saboteurs. Whirlwind Carter is yet another spaceman aping the Buck Rogers mold.

Despite their twisted art and simplistic story structure, Hanks’ comics are oddly compelling. When reading a Stardust or Fantomah story, you experience the fruits of an imagination unconstrained by conventional superhero tropes, because those conventions and tropes had not yet been established. Buck Rogers would never fight women with cannons on their heads, nor would Superman ever melt a criminal’s head into his body, but these things appear in the pages of a Hanks’ comic, daring the reader to question them.

Fletcher Hanks created 51 comics stories before leaving the industry in 1941. No one knows why Hanks quit comics, but certainly his alcoholism and general disdain for long-term employment played a part. Other artists would continue the stories of some characters like Space Smith and Fantomah with more traditional comic art and storytelling. But without Hanks’ weirdo touch, those later comics are boring and pedestrian.

Little is known about Hanks’ life after 1941. He moved back to his hometown of Oxford, MA and served on the town commission in the late 1950s. In 1976 his frozen body was found on a park bench in Manhattan. Fletcher Hanks died cold, alone, and penniless.

For decades, Fletcher Hanks and his work remained forgotten and unknown. Occasionally, alternative-press publications like Art Spiegelman’s Raw would republish his stories. Hanks remained an oddity, cult-figure, and an inside joke among fans of obscure comic book minutiae.

His legacy hit the mainstream (or as mainstream as these things get) in the early 2000s. In 2006 Dan Nadel compiled Art Out of Time: Unknown Comic Visionaries 1900-1969. This collection of forgotten cartoonists featured Hanks along with many artists. In 2007, cartoonist and editor Paul Karasik and Fantagraphics Books published a collection of Hanks’ works titled I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets. Karasik had tracked down Hanks’ surviving family, and it is through his interviews with them (especially Fletcher Jr.) that we know what we do about Hanks. This book was followed by another collection, You Shall Die by Your Own Evil Creation, in 2009 and Turn Loose Our Death Rays and Destroy Them All! in 2016, which collected the entirety of Hanks’ work.

The original work of Fletcher Hanks is all in the public domain now. While it is unlikely that he will ever be a household name like Stan Lee or Jack Kirby, his bizarre legacy inspires artists and writers today. Stardust has appeared in a shockingly wide variety of modern comics—from FemForce, to Savage Dragon, to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. In 2016 the jungle goddess appeared alongside Red Sonja and John Carter in the Worldscape comic, based on the Pathfinder RPG. Of course, in 2021 JLHB Polytechnic published Leopard Women of Venus which brings the brutal strangeness of Fletcher Hanks to the Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG. Despite his unpleasant life and lonely death, the comics Fletcher Hanks left behind continue to inspire creators across many disciplines.

And check out the Fletcher Hanks-inspired DCC-compatible Leopard Women of Venus!