KATSUHIRO OTOMO: A WORLD OF DESTRUCTION

For fans of anime and manga, the name Katsuhiro Otomo sits well above the rest.

As one of the most prolific writers and animators of either medium, the master creator is hailed amidst his contemporaries - Hayao Miyazaki, Mamoru Oshii, Shinichiro Watanabe - first and foremost for his revolutionary manga-turned-movie, Akira, released respectively in 1982 and 1988 to worldwide acclaim. His other works moreover, however lesser-known, only help to prove his world-annihilating genius and combustible graphic style - with inclusions that, while faltering to hit the colossal heights of Akira, have nevertheless changed the landscapes of manga and anime forever.

Born in Japan’s northeast region of Tohoku, in the city of Tome-gun located in Miyagi Prefecture, Katsuhiro Otomo grew up miles away from anything remotely capturing the gargantuan cityscapes of many of his works. A lover of film with a penchant for animation, Otomo spent many of his weekends travelling to the city of Sendai in order to catch the latest pictures, stating in a foreword to a 1996 reissue of his seminal graphic novel, Domu: A Child's Dream, that when “[he] was in highschool [he] was so crazy about movies [...] Movie-going was [his] main hobby in those days”.

Fuelled by this affinity for film and his skill with pencil, Otomo travelled to Tokyo after graduating in order to establish a career in manga artistry. Looking to prove himself as a budding mangaka (a person who draws manga), Otomo would lend his creative vision to such works as Okasu (1976), Round About Midnight (1977) and Nothing Will be as it Was (1977); cementing himself as an upcoming talent and planting the seeds of his revolutionary style. According to a 1980 review of his early works by the Asahi newspaper, Otomo’s impact on manga was equateable to the emergence of the ‘New Cinema’ movement in Hollywood, demolishing “the old [...] style of filmmaking to usher in a fresh style of movie production in America. Katsuhiro Otomo from provincial Tohoku, came to Tokyo to create a new comics style and shattered the conventions of traditional manga”.

Following some of his most celebrated works, this article will discuss and distinguish the artistic accomplishments of the esteemed, Katsuhiro Otomo. From his manga to his movies, we at Sabukaru invite you to revel in the revolutionary feats of one of our favourite artists - beckoning you to enter and absorb the intricate realities of Japan’s most destructive visionary.

Fireball

With an appetite for horror and science fiction in an industry that lacked anything resembling the futuristic epics of Stanley Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange), the dystopian worlds of Philip K. Dick (The Man in the High Castle, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) or William Friedkin’s cinematic nightmare, The Exorcist - Katsuhiro Otomo had all the proverbial balls in his corner and was ready to strike. And strike he did with a slew of renowned comics that set the precedent for his anarchic, mind-bending, city-destroying tone, while laying the conceptual ground-work for his more distinguished pieces.

One of these comics was the unbridled (and unfinished), Fireball, published in Action Deluxe magazine in 1979. Introducing a rebellious motif found in much of Otomo’s art, Fireball presents a city at war with itself as a group of freedom fighters attempt to expose the governance of futuristic city under the rule of a supercomputer called ATOM. Featuring a tyrannical military-esque leader - ambivinantly titled, The Director - the comic follows the tale of two brothers, one on the side of freedom, and the other on the side of governance. The latter of whom is revealed to harbour psychic superpowers which, when threatened, are terrible and catastrophic. With a cataclysmic climax akin to that of Otomo’s later works, Fireball remains an unfinished masterpiece which, according to the creator in a foreword to a republication of the comic, was due to him “of course, [running] over the deadline”.

Although incomplete, and only tinkering with the troupes that would later be regarded as seminal to his overall portfolio, Otomo’s Fireball endures as a substantial leap in manga artistry. With a preference for depicting more realistic character designs than most other manga at the time, the inclusion of psychic powers, freedom fighters and an Orwellian governmental system - Fireball laid the groundwork for things to come, and set the stage for Otomo’s first notable and widely celebrated effort, Domu.

Domu: A Child’s Dream

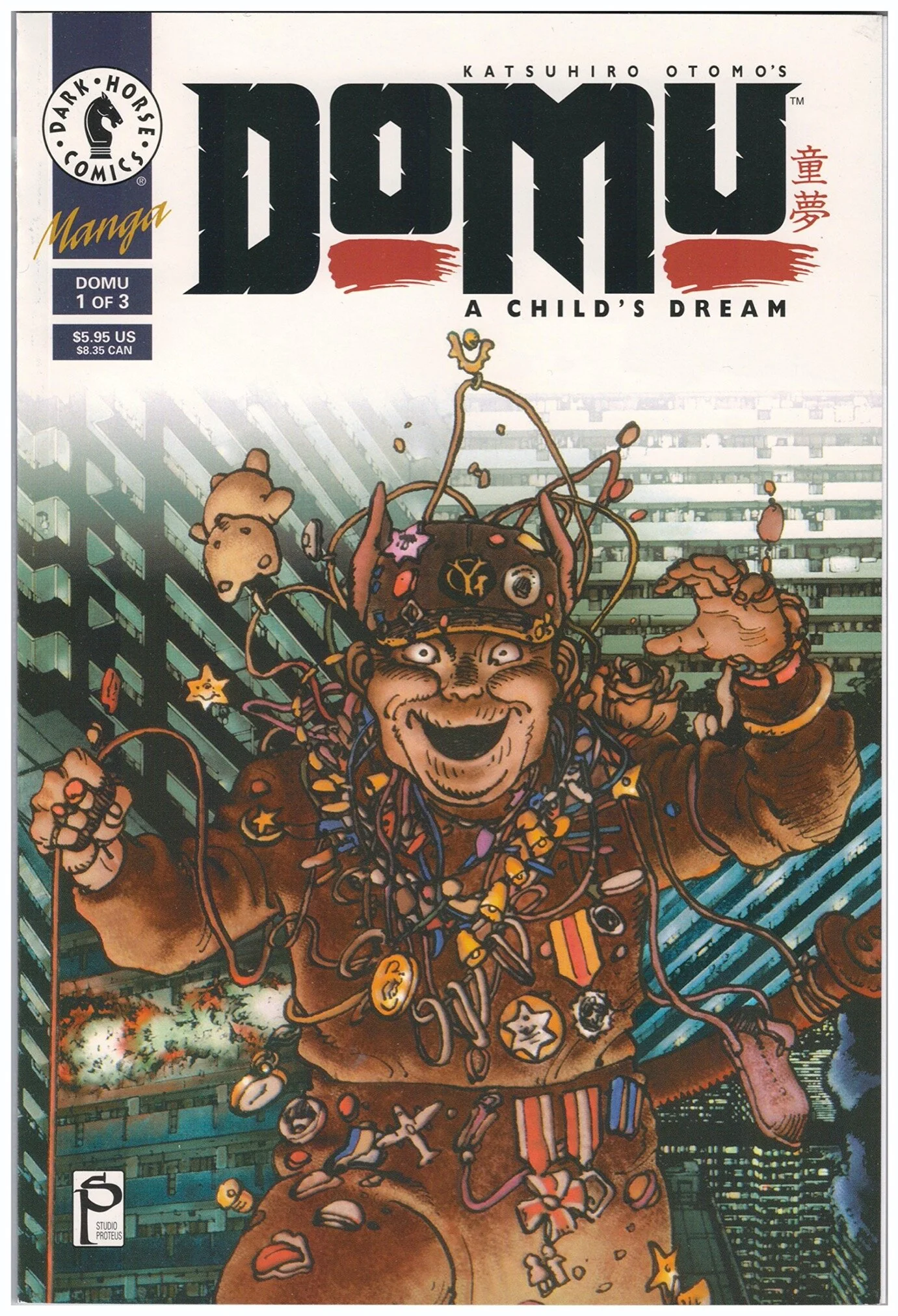

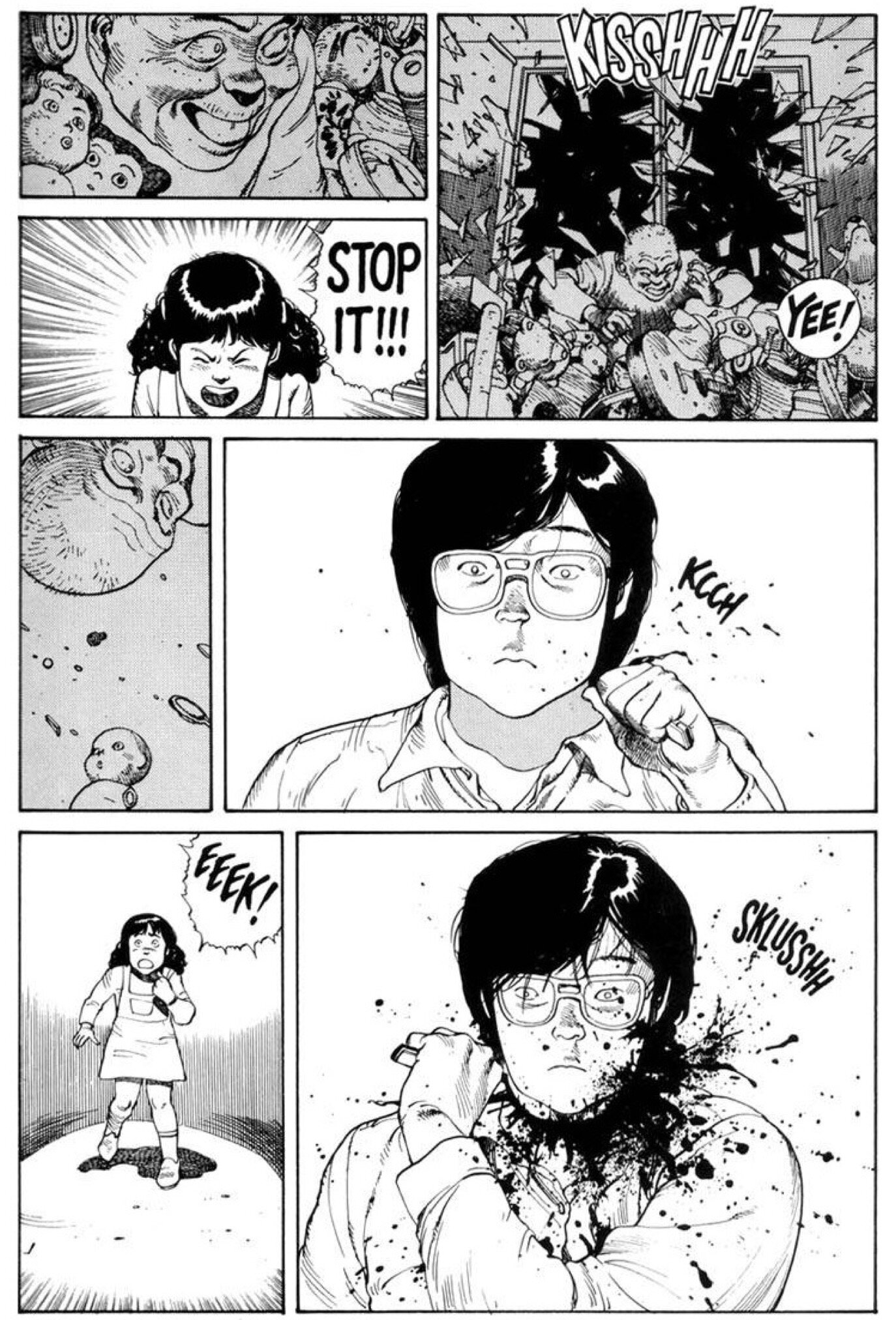

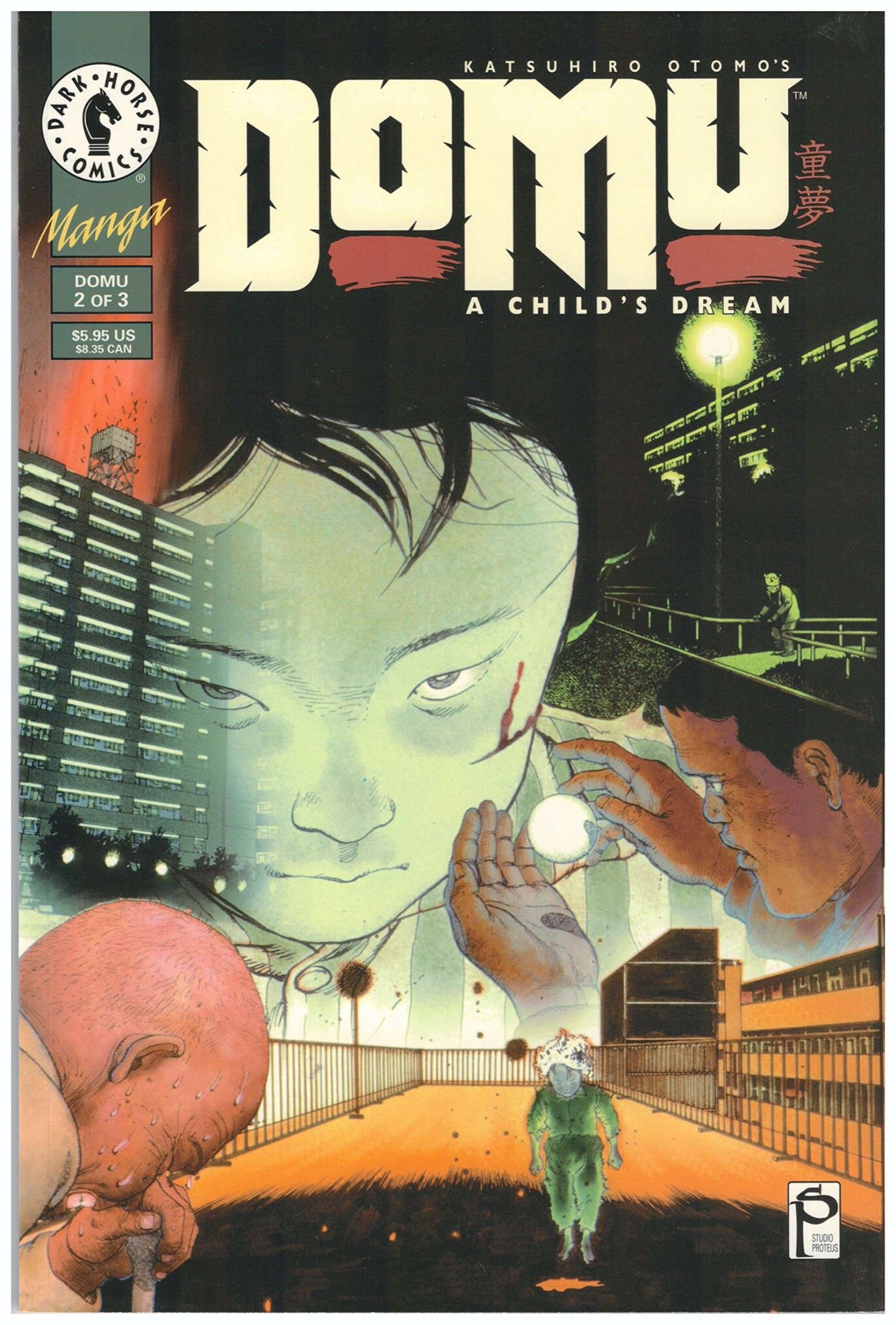

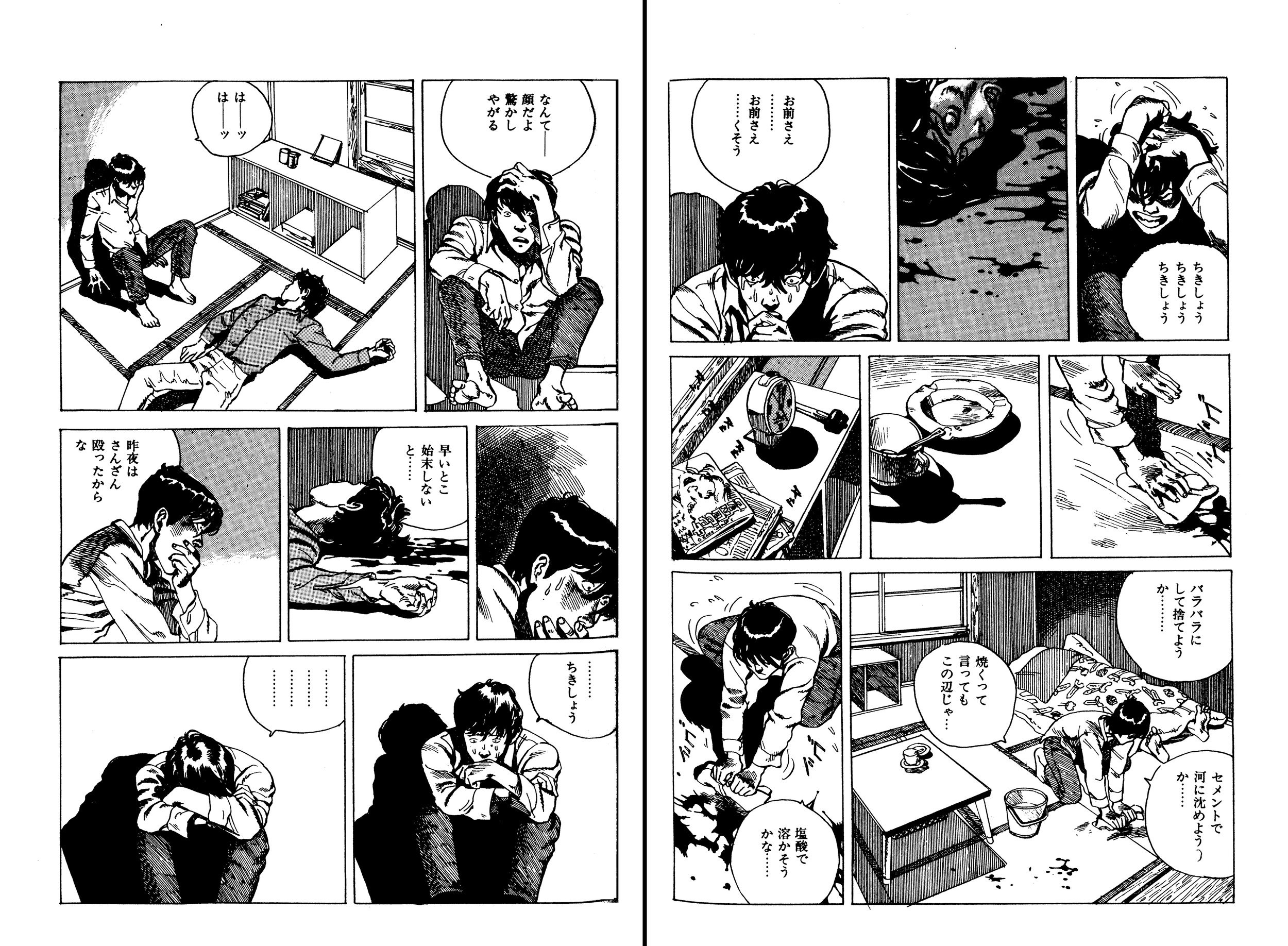

Selling over 500,000 copies in Japan and winning a multitude of awards - including the prestigious, Nihon SF Taisho Award (being the first manga to win said award) - Domu: A Child’s Dream is the tale of a housing block in Tokyo plagued by a slew of horrific “suicides”. Yet, after Inspectors Yamagawa and Takayama investigate the chain of deaths, they begin to realise that not all is as it seems; discovering that the victims are seemingly coerced to their deaths by some sort of supernatural being. Indeed, over its serialization in Futabasha's Action Deluxe between 1980 and 1981, it is revealed that the housing complex is being haunted by the psychotic actions of a superpowered old man named Old Cho. With the ability to inhabit people’s minds and utilise telekinetic powers, the old man - seemingly infantile in his sensibilities - causes the inhabitants of the complex to perform horrific actions, at one point even causing a drunken father to shoot his own son.

As the investigation continues to unfold before the Inspector’s eyes, a young girl, by the name of Etsuko, moves into the apartment building with her family. Inexplicably possessing similar powers to that of Old Cho, Etsuko uses telekinesis to save a baby pushed off a balcony by the former, as per his psychopathic tendencies. And as the tale unfurls, over the course of six chapters, she becomes somewhat of an adversary to the villainous old man, culminating in a psychic explosion of cataclysmic power as the two battle it out for the future of the inhabitants of the housing complex.

Containing a much broader array of artistic merit in a story which, although smaller in scale, seems larger in development than that of Fireball; Domu is a wondrous spectacle of the destructive menace of a child’s nightmare - terrible in its beauty and obliterating in its originality. Proving foremost Otomo’s penchant for harder, more brutal horror and his fascination for science fiction.

With its three volumes, released separately in 1995 in English and compiled in 1996 by Dark Horse Comics, Domu became one of the publisher’s highest selling comics of that year, and for good reason. Containing many qualities that would carry over into his later works - superpowered children, cataclysmic damage, unbridled rage - Domu: A Child’s Dream is a must read for any who love and seek out Otomo’s mastery.

Akira

1982, Tokyo. After briefly working on the anime film adaptation Harmagedon: Genma Wars, which was released a year later, Katsuhiro Otomo would begin working on his most influential and acclaimed work to date - the apocalyptic and duly exceptional, Akira.

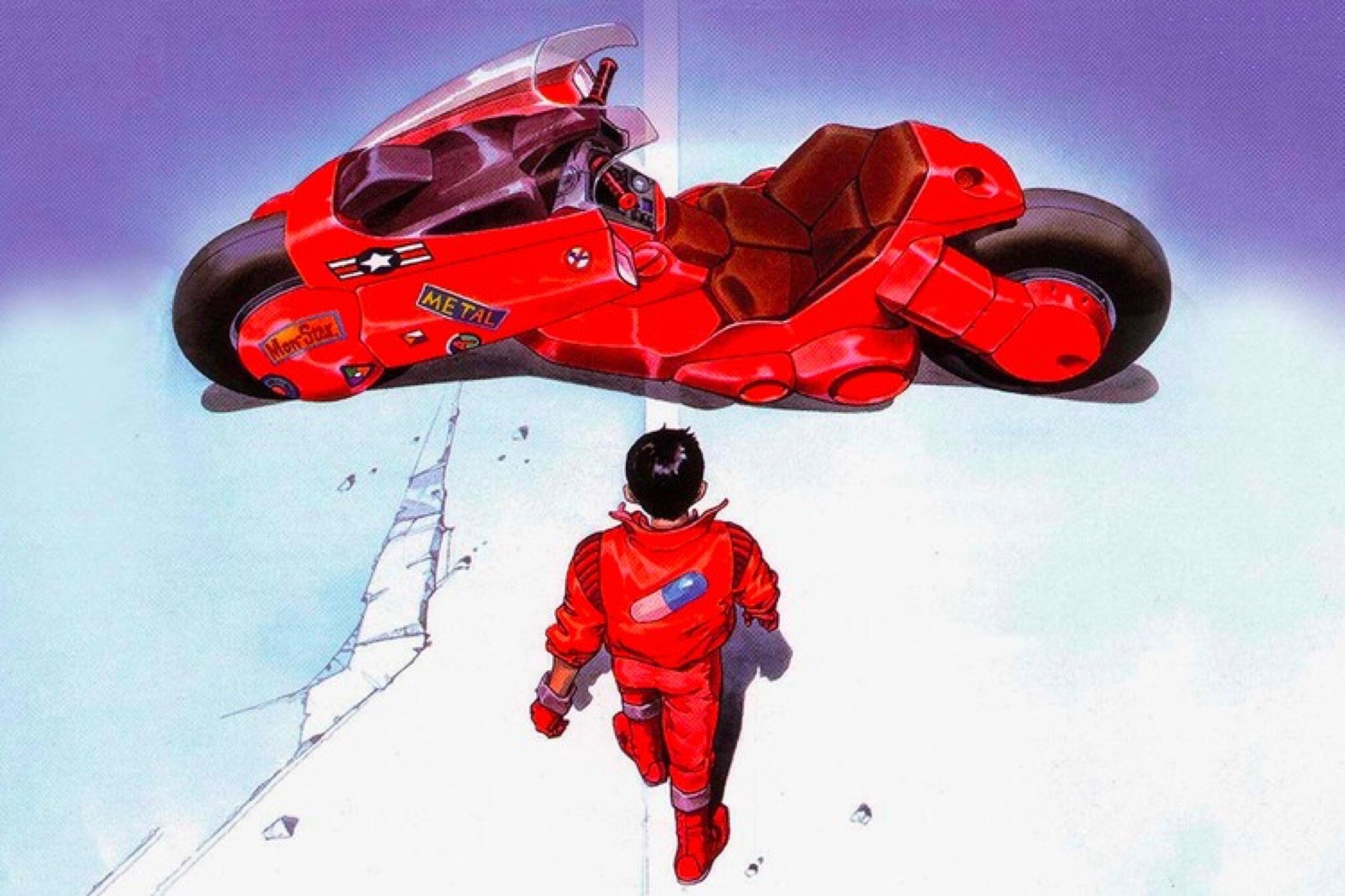

Known throughout the world, in large due to its seminal anime film adaptation, Akira began life as a serialised manga, published in the pages of Young Magazine from 1982 until 1990. Featuring a slew of expertly crafted characters in a post-apocalyptic Neo-Tokyo of 2019 (2030 in the English version), the graphic novel follows a group of anarchic teenage bikers who roam around the city causing havoc for police patrols and pedestrians alike. With the coolest cyberpunk attire and the slickest futuristic neon motorbikes, our heroes, Kaneda and company, seem settled in their rebel-without-a-cause fashion until their friend, Tetsuo, crashes into a seemingly helpless child. With no visible wounds, the child - known as Takeshi - is revealed to have extrasensory perception as well as other psychic abilities; abilities which seem to rub off on Tetsuo, leading him on a journey of self-discovery and self-destruction as he undertakes a search for the prophetic and titular figure known as Akira.

Soon falling ill to an unbridled inferiority complex about Kaneda, Tetsuo begins a psychotic downfall into monstrous deformation with cataclysmic consequences for all of Neo-Tokyo.

Falling in with a group of rebellious freedom fighters, Kaneda and the rest of our heroes seek to find answers to the mystery of Akira in the hopes of saving their friend, and indeed the world, from utter annihilation.

To speak praise of Akira’s monumental influence on the world of manga, as well as the world in general, would be misspent as most fans of the medium, of anime, or anything resembling cyberpunk or film culture will know of the seminal graphic novel (or at least the film). Instrumental at bringing western audiences to the prospect of manga, Otomo single-handedly thrust the Japanese-led medium into the hands of a global readership. Utilising its worldwide acclaim to create a coloured version of the novel for Marvel’s EPIC imprint from 1988 to 1994, which read from left to right as to assimilate with western comic books. Thus, giving us the iconic neon look of Neo-Tokyo and the futuristic aesthetic of Kaneda and his crew.

Openly citing influences from Star Wars, the comics of Moebius and the manga, Tetsujin 28-go, Akira is strewn with Otomo’s admiration for all things science fiction, while implementing the best facets of his previous work to boot. With the movie adaptation released in 1988, written and directed by Otomo himself, that largely eclipsed the impact of the manga, Akira stands as one of the most prolific creations of anime, manga and Japanese art as a whole; going on to inspire a world of western content - e.g. Rian Johnson’s Looper, Josh Trank’s Chronicle and the Duffer brother’s Stranger Things - while arguably setting the stage for franchises such as Dragon Ball, Naruto and even Pokemon.

If you haven’t read the manga, or at the least watched the film adaptation, then you are missing out on a masterpiece. Do so, at Sabukaru’s behest.

Neo Tokyo

During and after the publication and release of the seminal Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo continued to lead a varied and highly collaborative career, lending his creative talent to a number of anthologies of anime short films. One of these anthologies was the 1987, Madhouse led production of the science fiction collection known as Neo Tokyo - depicting three different segments each conceived under a different screenwriter and film director. The first of which, Labyrinth Labyrinthos, is written and directed by Madhouse founder, Rintaro - whose influence on Otomo has spanned a multitude of his works; as the man behind his debut gig in the aforementioned Harmagedon: Genma Wars.

The second, Running Man, conceived by Yoshiaki Kawajiri, depicts the tale of a racing circuit driver named Zack Hugh, whose track record spans an unbeaten 10 years. Culminating in a destructive death-race-style narrative in which Zack is shown to harbour explosive psychic abilities that lead to his final win and subsequent fatality at the “Death Circus” racing circuit.

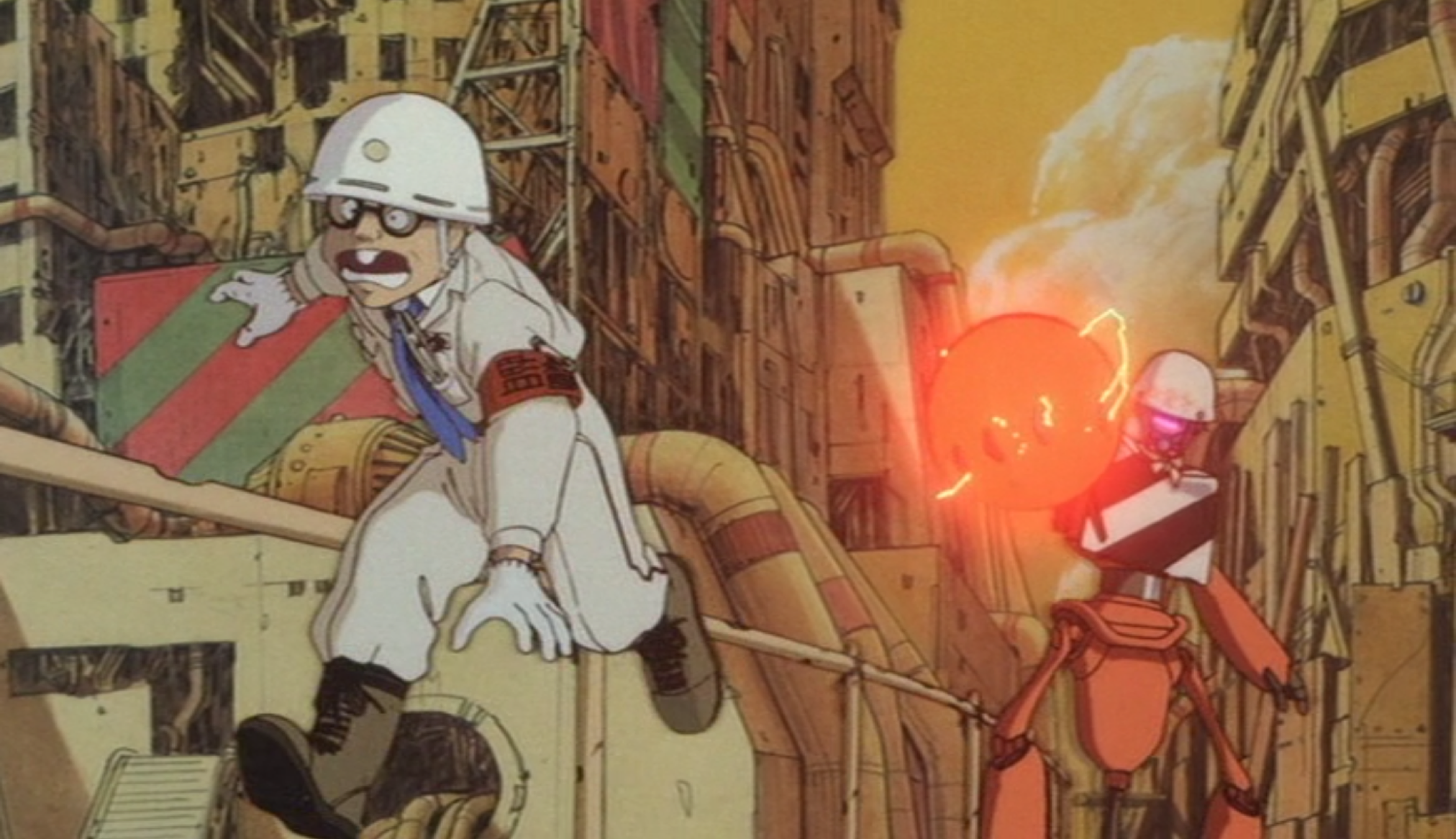

The third and most notable inclusion is Otomo’s Construction Cancellation Order, which pits a corporate salaryman against a malfunctioning foreman robot by the name of 444-1. After receiving news that, due to a political revolution and subsequent shift in governance in the fictional South American country of the Aloana Republic, the salaryman - Tsutomu Sugioka - must put a stop to the construction of a massive facility titled Facility 444. Yet, as per the malfunctioning 444-1 - whose defection has it sacrificing myriad construction robots in a futile attempt to finish the facility - Tsutomu’s objective is rendered more complex. Leading our corporate hero on a fight for survival in his attempt to fulfil his company orders.

A cautionary tale about man’s reliance on technology, Otomo reiterates here his penchant for destruction and distaste for authoritative control - as the world of Construction Cancellation Order is fueled by political upheaval and demolished due to the recklessness of greedy corporations. A fun romp with poignant themes of environmentalism, corporate dominance and technological insurgency, Otomo concludes the Neo Tokyo anthology with style and wit - both of which have hardly aged a day.

Robot Carnival

Another of Otomo’s anthology collaborations, APPs 1987 release, Robot Carnival, features a slew of anime shorts from an array of Japanese filmmakers all encompassing the theme of robots. Curating work from Koji Morimoto and Takashi Nakamura to name a few, with Otomo writing and directing only the opening and ending segments of the piece - both of which are wonderfully explosive.

Presenting a post-apocalyptic wasteland, in which a monolithic travelling carnival is performed by a diverse array of automata, Otomo’s opening and closing segments succinctly introduce the theme of robots, while expounding upon the consequences of humanity’s obsession with technology to an explosive degree.

Although not much else need be said about Otomo’s inclusions, they appropriately bookend the stylistic and smart showcase of anime talent on display, while adding a sense of prominence to the overall anthology. With notable musical additions by Studio Ghibli’s go-to composer, Joe Hisaishi, Robot Carnival is a sound collection of anime achievements, and an intriguing watch for fans of Otomo and the medium in general.

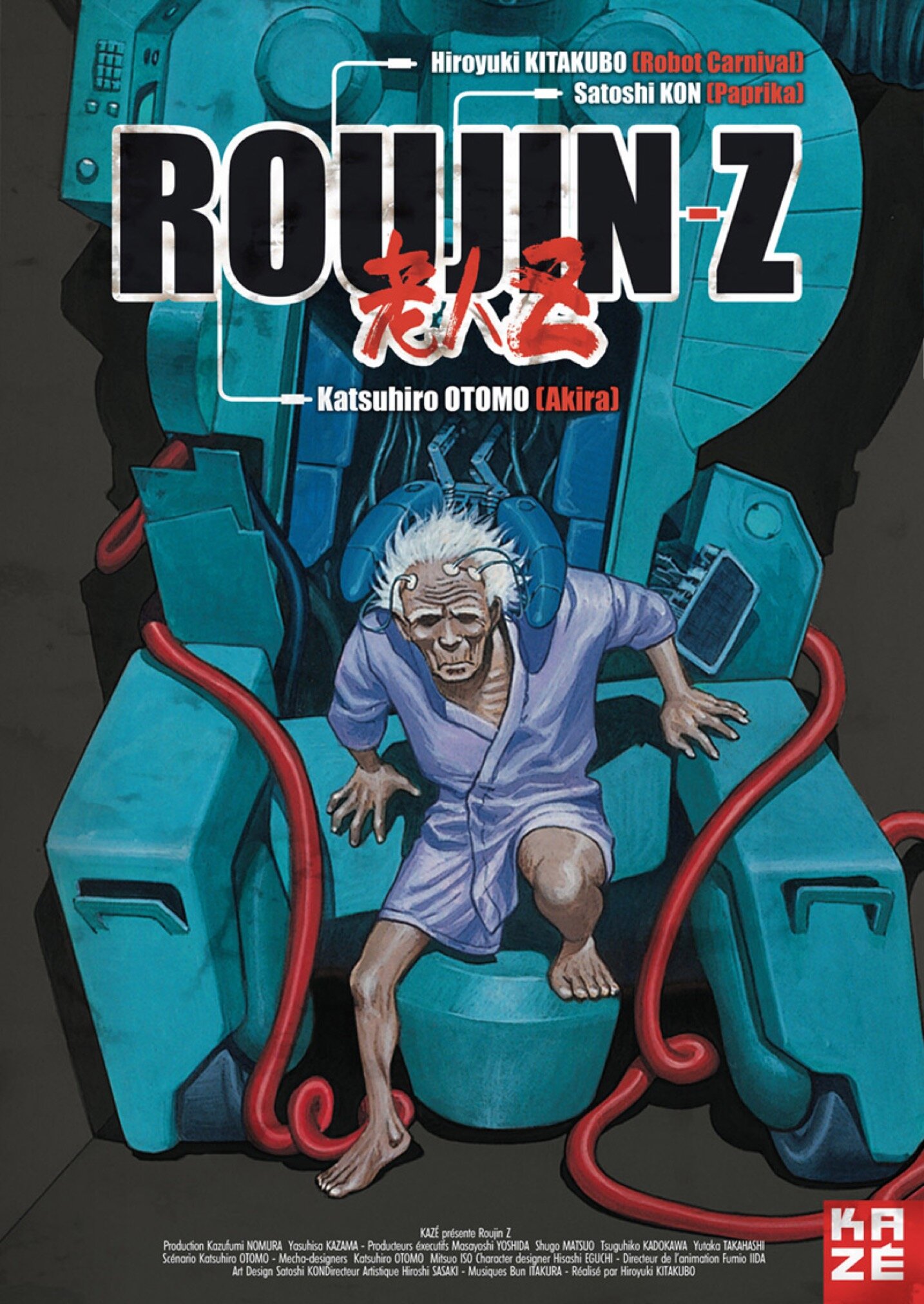

Roujin Z

A futuristic and largely comedic tale about man’s growing reliance on technology, Hiroyuki Kitakubo’s 1991 anime film, Roujin Z, depicts the story of an overzealous young nurse whose patient - an 87-year-old dying widower named, Kiyuro Takazawa - is wired up to an experimental machine known as the Z-001. A hospital bed with robotic features, the Z-001 is shown to be able to completely take care of any and all patients in its comfort; boasting medical and habitual care to the highest degree, as well as integrated entertainment technology such as television, computer gaming and online communication. Made seemingly pointless in the advent of this machine, the nurse protagonist, Haruko, feels that her ex-patient is in some sort of danger as per the experimental nature of the machine.

As the story pans out, it is revealed in gloriously mecha fashion that the machine is in fact an experimental computer designed for military warfare. While still inhabited by Takazawa, the machine begins to evolve and upgrade itself, forming a simulated personality and developing empathy for its bedridden patient. Coexisting in connection with Takazawa’s brainwaves, the machine assumes the identity of his late wife, Haru, and the two commit to a calamitous journey to the beach in a last ditch effort to relive their younger years.

Written and conceived by Otomo, Roujin Z is a fitting continuation of the themes typical to his stories. Presenting a cautionary tale of the morality of robotics, humanity’s overbearing want to progress in military warfare and the destructive consequences of unethical experimentation - the film is exceedingly Otomo in its ideas. Yet, it also endeavours to raise awareness to the way in which we, as a species, treat our elderly; seeing them as useless, wasteful products of ageing and nothing more than a foreboding reality of the inevitability of death. Otomo makes clear his belief in the importance of caring for our elders, proving their uses by implementing many that are hospitalised alongside Takazawa in ways that are both hilarious and narratively sound. He shows that old folk should never be seen as something disposable as per the disastrous results of the Z-001 experiment.

In typical Otomo style, the film climaxes in an explosive spectacle, with the military characters punished for their hubris and our heroes rewarded for following the path of righteousness. Although relatively unknown in the larger scope of Otomo’s work, Roujin Z is a great, confined tale of AI consciousness, and how we should respect our elders no matter their capacity.

Memories

Following up Roujin Z, and his prior stints in anthology work (Neo Tokyo, Robot Carnival), Otomo would go on to put together arguably his greatest achievement in collaborative animation - executive producing, along with Madhouse, the excellent Memories in 1995. Another three piece collection of short films, Otomo enlists a slew of illustrious anime talent to take part in this renowned selection of work; including the late, great Satoshi Kon - who, while eventually would become the director of an amazing array of films (e.g. Perfect Blue, Tokyo Godfathers and Paprika), began work as an uncredited art assistant on Otomo’s Akira and a key animator on Roujin Z.

Directing only one of the three short films - Cannon Fodder - Otomo would lend his vision to all three of the science fiction wonders, developing the story for Koji Morimoto’s nostalgic dream, Magnetic Rose (featuring a screenplay by Kon), penning the script for Tensai Okamura’s Stink Bomb and writing and directing the final segment himself (the aforementioned Cannon Fodder). Being the mind behind anthology’s conception, it’s no wonder that each of the segments features a cautionary tale depicting man’s inability to refrain from destroying oneself.

Magnetic Rose presents the tragic story of missing opera singer, Eva Friedelen. Trapped by a slew of sentimentality and a whimpering of nostalgia for her past life, Eva is encased in a giant space station, orbited by a spaceship graveyard in the infinite darkness of deep space. Discovered by a space salvage freighter - inhabited by a variety of colourful characters - our protagonists, Heintz and Miguel, take it upon themselves to seek out treasures within the ship and uncover the mystery of its mysterious distress signal.

Only unearthing a foray of deep-set trauma with implosive consequences, the two succumb to a battle of wits with the ghostly Eva and their own repressed memories as they attempt to escape themselves and the confines of the Magnetic Rose. Arguably the best in the anthology, and the precursor to Kon’s dreamlike portfolio of work, Magnetic Rose shows, in nightmarish fashion, the infectious lull of nostalgia and what befalls those who fail to let go of the past.

The last segment of the anthology, Cannon Fodder, is perhaps the most pertinent inclusion, being wholly conceived by Otomo himself. Featuring a bombastic steampunk city strewn with cannons and lavished in a pseudo-soviet art style, Cannon Fodder tells the tale of a world at war - the reason for which, or whom our characters are at war with, is unclear. Following a young school boy - who dreams of becoming part of the violent system of cannon firing - and his father - who, as a mere cannon loader, suffers at the oppressive nature of the city’s communistic regime - the story aims to denounce the nature of tyranny and dispel the hypnotic sanctimony of propaganda.

With poignant implications as to the pointlessness of war, the disparity of equality in an oppressive political regime, and a diverse set of animation styles from hand-drawn to 3D, Otomo exhibits an intriguing addition to an already alluring set of anime pieces.

Metropolis

Venturing into the new millennium, Otomo’s artistic passion would continue with a couple of enticing anime films that, although faltering in comparison to the monumental Akira, still stand the test of time as innovative and intriguing pieces of work.

The first of which is the Rintaro led 2001 adaptation of Osamu Tezuka's 1949 manga, Metropolis. Inspired by the 1927 german expressionist film of the same name by pioneering filmmaker, Fritz Lang, Metropolis depicts the story of a world strewn with robots, those of which are seen as inferior to the largely disillusioned population of humans. Following a boy by the name of Kenichi, who in an unlikely turn of events, becomes enthralled with a new, unfinished super robot named Tima, the film attempts to explore the complex notions of robotics and what it means to be human. In an exciting, emotive and entertaining story about identity, memory, friendship and love, Metropolis works to stimulate all those enticed by complex dystopian science fiction while also catering to the hearts of younger viewers concurrently. As per Tezuka’s original art style, the animation remains incredibly faithful to his revolutionary techniques, presenting a beautifully vibrant world that, while adult in content, is wonderfully childish and playful in tone.

With the screenplay adaptation written by Otomo himself, this is by and large a version of Tezuka’s classic story that would satiate the artistic resonance of the renowned “Godfather of Manga”.

Steamboy

The next notable anime film under the vision of Otomo is the steampunk action jaunt, Steamboy, produced by Sunrise and released in 2004. Written and directed by Otomo, the film depicts 19th century England in the heart of a semi-fictitious, industrial revolution, featuring steampowered technologies of all kinds.

Ray Steam, our main protagonist, is a budding engineer, and the son of a leader in steam-powered innovation. In an adventure that spans Manchester through London, Ray is thrust on an epic romp of action and genre-commitment, as Otomo details a comprehensive look at a world running on steam. With a cataclysmic, city-destroying climax that is almost expected as per the nature of its director, Steamboy is a wonderful action-blockbuster of epic proportions. Boasting clean animation, a consistently intriguing aesthetic and a provocative story about the consequences of technological progress - Otomo’s film explores, in spades, the lengths humanity will go to exceed in newfound weaponization.

Short Peace: Combustible

A multimedia project composed of four short films produced by Sunrise and Shochiku, and a video game developed by Crispy's! and Grasshopper Manufacture; Short Peace is a 2013 anthology of diverse narratives, surrounding the theme of Japan, told through intriguing and largely experimental animation techniques. Featuring the likes of Koji Morimoto, Shuhei Morita, Hiroaki Ando and of course, Katsuhiro Otomo, the collection received a number of accolades for its innovation and art style; including the Grand Prize at the 16th Japan Media Arts Festival for Otomo’s Combustible and a nomination for Best Animated Short at the 86th Academy Awards for Morita’s Possessions.

At only 13 minutes long, Otomo’s segment is strewn with vibrant colour and visual commitment to the art style of the Edo era (1603-1868) of Japan. Depicting the life of a young aristocratic woman, Owaka, who is set to be engaged to a wealthy suitor instead of her true love, Matsukichi - a childhood friend and rebel without a cause - Otomo presents, lavishly, his love for the Edo aesthetic through narrative tragedy and historic tribulation. Over the course of the film, Owaka despairs over the future monotony of her life, her forbidden love and the myriad meaningless wedding gifts now in her possession. In a tragic accident, our heroine throws a fan over to a burning lamp which proceeds to set alight, thus beginning a catastrophic fire which spreads throughout the entire building.

Loosely based on the historical event, The Great fire of Meireki (1657), Combustible is a sombre look at the archaic marriage traditions of Edo era Japan, while also being a love letter to the tactile art style of many of the period’s pieces. Speaking in an interview with US magazine, Animation Magazine, in 2012, Otomo affirms that “[he’s] always wanted to create a story about Edo”. That the “theme of [Combustible] is based around classic tales from the Edo era such as Yaoya Oshichi and the comic Kaji Musuko, which are commonly used for Kabuki or Joruri programs. [He] wanted to take that old theme that [they] used to have in Japan 300 years ago, and describe [it] with recent technologies, in anime form”.

Infinitely successful in his approach to reimagine the traditional Japanese form in anime style, Otomo proves that, while enamoured for his previous iconography, his want to create new and innovative art remains as strong and impassioned as ever.

Future Endeavours

Since Short Peace, Otomo has released little work of note yet continues to influence numerous films, television shows, comics, fashion and music to date. His seminal style and approach to anime and manga have remained as revolutionary as ever and his love of innovation and experimentation lingers as a progressive attribute to many who devour his eclectic body of work.

With Otomo reportedly helming a new Akira anime series, while prepping his eagerly awaited anime film Orbital Era, we are sure to witness more from the groundbreaking mangaka and filmmaker at some point in the near future.

What’s more, although years in development, the live-action adaptation of Akira has recently propelled forward in production with Thor: Ragnarok director, Taika Waititi, slated to direct. However, with his newfound commitment to helm a new Star Wars film for Disney, it’s likely that the live-action Akira will face another delay amidst its almost 20-year development period. And while a live-action movie will never manage to eclipse the monumental impact of Otomo’s original graphic novel and anime film, we do hope it does it justice in some part.

Here’s to the great, Katsuhiro Otomo - our rebellious leader in cyberpunk Neo-Tokyo. A master mangaka, an iconic filmmaker and a proven visionary to boot.

About The Author

Simon Jenner explores meaningful storytelling through film and media, occasionally producing writing along the way.