Emerging Markets: The Flying Eye

Following a long tradition of the symbolic use of the eye, the Jimi Hendrix poster is becoming a historic reminder of the hippy days of the ‘60s

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

Oct 19, 2022

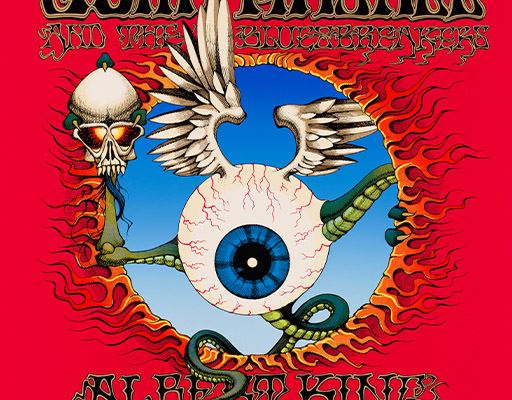

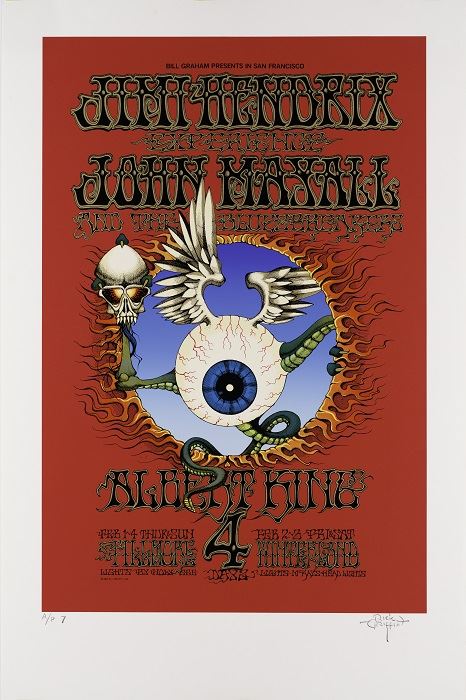

The original artwork for the Mona Lisa of psychedelic posters was up for sale on October 15 at the Festival of Rock Posters at the Hall of Flowers in San Francisco. Its creator, Rick Griffin, was literally the poster boy of San Francisco’s wheat paste rock poster scene, designing many of the iconic images that have come to define the hippy era. His 1968 Flying Eye Jimi Hendrix poster is perhaps the most famous of them and encapsulates the aesthetics of psychedelic art.

Rick Griffin, Jimi Hendrix poster

Born in the psychedelic seventies, rock concert posters were vehicles of a fresh and exuberant underground aesthetic, taking their roots from art nouveau, the ecstatic imagery of Fidus (Hugo Hoppener), abstract art, and the colorful visuals of the hallucinogenic experiences provided by LSD, mescalin, and psilocybin. The brash and bright colors of pop art owe much of their fresh palette to kaleidoscopic acid trips. The scrambled collages of sixties and seventies multimedia, and the computer-generated visual effects of contemporary movies owe much of their aesthetic to the tumbling chaos of hallucinatory fragmentation, to the ethereal expansiveness and writhing, unearthly motion of the trip. Griffin’s flying eye poster captured beautifully the extraordinary abandonment of the LSD experience – an intense and sensual combination of frenetic, tumbling freedom from the dull restraints of ordinary time and space, a deluge and jumble of beautiful and bizarre imagery, and a deeply felt connection to the numinous. It is an iconic image of the era – perhaps, the iconic image of the era.

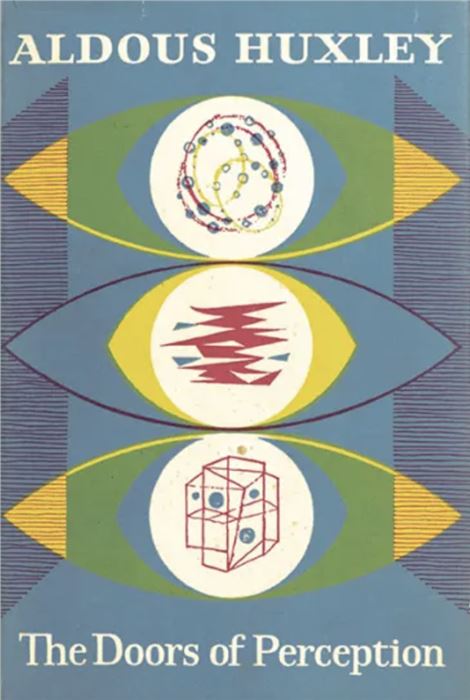

John Woodcock, The Doors of Perception

Griffin’s flying eye had multiple roots, not least the cover art of the 1954 first edition of The Doors of Perception, created by artist John Woodcock to illustrate Aldous Huxley’s account of his use of mescalin, which probably would have been seen by Griffin in the hands of his friends in psychedelic California. Woodcock’s cover was a trio of abstract blue, yellow, and green eyes, with their pupils replaced by circles of connected atoms, a vaguely Aztec, jagged, and almost figurative red pattern with three blue triangles, and a crude geometric diagram resembling the strange illusions of M.C. Escher, with blue circles confined within the structure.

But perhaps Griffin was thinking of the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote of his rapturous communion with the landscape and had visions of being one with nature: “Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball. I am nothing. I see all. The currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

Griffin certainly admired the work of hot rod artist Kenneth Howard, best known as “Von Dutch,” who designed his own flying eye as a symbol branding his unique style of pinstriped decoration on custom cars and motorcycles as early as the 1950s. Howard was notoriously indifferent to trademarks and made no objection when Griffin adapted his eye image for the famous Hendrix poster, which tied California’s underground hot rod scene to the surfing culture of the beaches and to the acid tests of the Grateful Dead.

Tomb of Pashedu (Photo by permission of Kairoinfo4u)

But the flying eye had ancient antecedents. Its history began at the heart of the mythology of Egypt, where it was written that the sky god Horus’ eye was stolen by his rival Set, who trampled it and ate it. The god Thoth restored Horus’ eye to him, and brokered a peace with Set. The eye was commonplace among ordinary Egyptians as a decorative amulet, and was painted on the walls of tombs, and the prows of boats.

Emblem from the Hieroglyphics of Horapollo

Among the humanist intelligentsia who disseminated a fascination with Egyptian hieroglyphs during the renaissance, the famed author and artist Leon Battista Alberti was fascinated with the power of symbolic meaning, and designed decorative friezes of his own language of images to adorn the buildings he designed for his Italian masters. He used the flying eye as his personal emblem, ordering bronze coins to be cast, decorated with a flying eyeball, which he used as novel tokens for friends and new acquaintances – handing them out like a collectible business card to be added to their collections of curiosities. The custom of giving coin tokens still exists among certain modern fraternal organizations, including the freemasons, who use the eye as a symbol of God.

Freemason Coin

Alberti’s image was typical of a new form of literary and visual art called the emblem, which became extremely popular between the 16th to the 18th centuries. Born from the new and popular interest in recently rediscovered hieroglyphics, these emblems were allegorical images ranging from figurative pictures to cosmic diagrams, accompanied by brief interpretive epigrams, usually in a spiritual vein. The emblematic eye was often deployed in decorative art as a visual metaphor for the Christian god, whose omniscient vision saw and knew all things. In 1525, Jacopo Pontormo painted his Supper at Emmaeus, now displayed at the Uffizi, Florence. Originally a triple-faced head was painted above Christ, but the triple head was forbidden during the counter-reformation, and this was painted over by copyist Jacopo da Empoli with an all-seeing eye in a triangle – an acceptable image of the trinity, more formulaic, more geometrical, more in tune with a mathematical approach to metaphysics.

Jacopo Pontormo, Supper at Emmaus

Both Griffin and Howard were certainly familiar with the image of the floating all-seeing eye watching from the levitating capstone of the pyramid on the ubiquitous one-dollar bill, which was added to the design in 1935 during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. The pyramid and the eye first became part of America’s national symbolism in 1782 when it was included in the design of the reverse of the Great Seal – not as a hermetic symbol of illuminati domination, but as a commonplace emblem of the omnipresence of God, whose watchful blessing was invoked upon the endeavors of the new country. Enthusiasts for conspiracy will be disappointed that the earliest historical record of the use of the eye as a masonic symbol was fifteen years later in the 1797 “Freemason's Monitor” by Thomas Smith Webb.

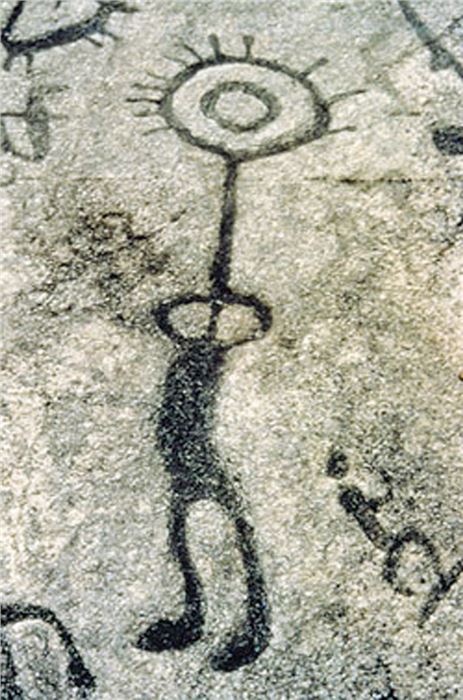

The Peterborough Petroglyph

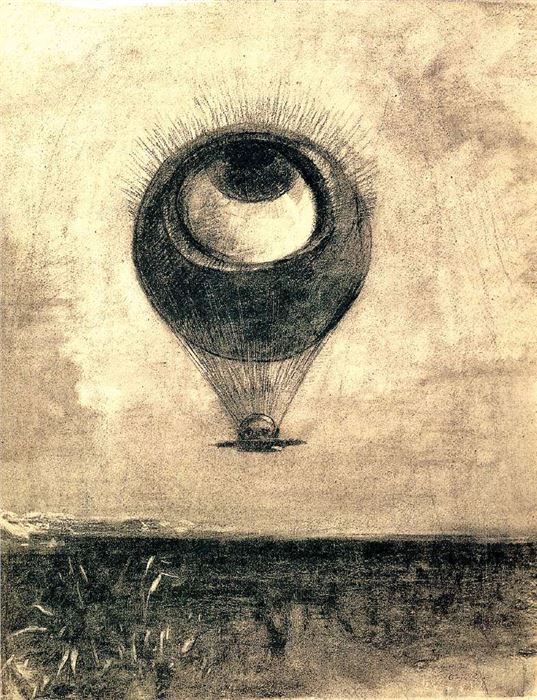

In the Americas, the eye was used by natives in relationship to the sun as the eye in the sky. In 1954, an extraordinary 90′ x 120′ spread of petroglyphs was discovered in the forest near Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, carved into a sloping outcrop of white marble. Among the chaotic frieze of ancient images was a superb picture of a human figure whose head was replaced with a giant eye which he held aloft on a tall stem extending from his shoulders. The image is strikingly similar to symbolist painter Odilon Redon’s The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity, although Redon could not possibly have seen the petroglyph, having died in 1916. But Griffin was keenly interested in native cultures, and surrealism, and psychology, and it is tempting to connect the images together in his work to represent the synthesis of native spirituality with the burgeoning contemporary theosophist syncretism, and the acid aesthetic that permeated hippy mysticism.

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity

Now, the hippy days are metamorphosing into history. The last living memories of the dramas of the 1960s are passing with their participants, but the visual imagery of the period retains the spirit of the vital days of the summer of love. When Griffin’s Flying Eye was plastered onto the telephone poles and billboards of Haight in the summer of ’68, it was also glued into the iconic history of visionary and psychedelic art.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

.Jpeg)