Forever Lost in Dream: The Art of Odilon Redon

Painting the fantastical and nightmarish, at first mainly in charcoals, Odilon Redon’s late recognition ultimately earned him the title of a precursor to surrealism

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Feb 16, 2024

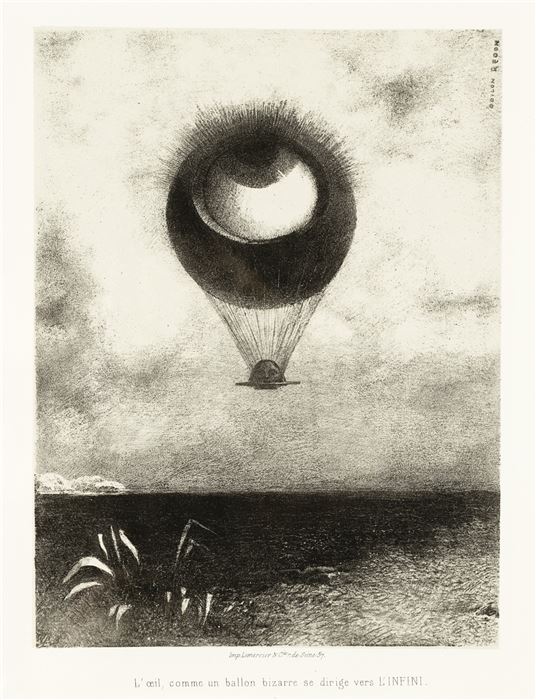

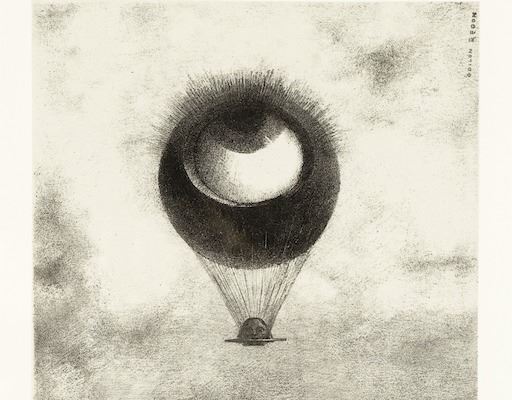

A plant blossoms into human heads, a forlorn Christ stares out from perpetual darkness, an object resembling a hot-air balloon with a cyclopean eye floats above a body of water – Odilon Redon’s earlier work plays out like a fever dream. But these scenes of stygian gloom eventually would explode with color, morphing into ethereal scenes of beauty. Redon is known as a symbolist, but the vast imagination the French painter possessed and drew from to create his pieces, has led many to consider his work as a pre-cursor to surrealism.

Odilon Redon, To Edgar Poe (The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon, Mounts toward Infinity), 1882, lithograph, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Odilon Redon was born in Bordeaux in 1840. He was an extremely introverted child, wandering the hallways of the family’s 16th-century manor house. The estate on which it was situated was dull and dreary, and the young Redon immersed himself in art, drawing frequently. At fifteen years of age, he began his formal study of painting, but due to parental pressure from his father, switched his focus to architecture. This shift did not bring success to Redon, and neither did his subsequent foray into sculpture. His father finally allowed him to pursue painting properly, and the young artist went to Paris in order to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. Although, his time at the institution was short-lived, as the strict academic environment did not suit him, swiftly putting an end to his days of formal study.

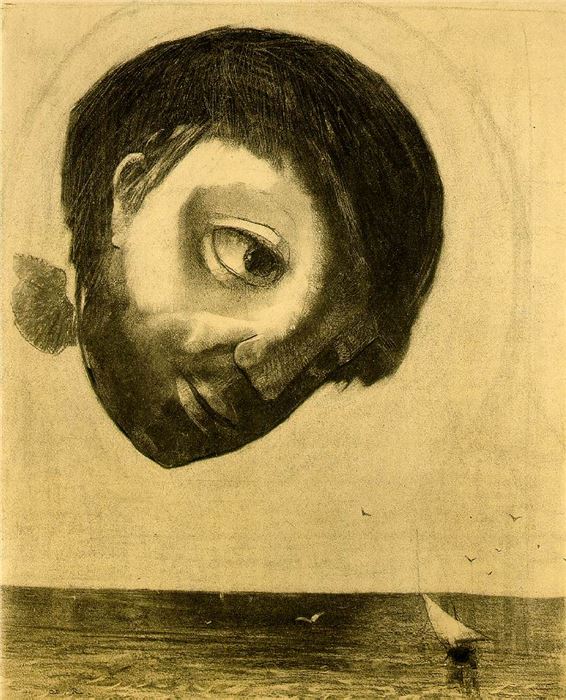

Odilon Redon, Guardian Spirit of the Waters, 1878, various charcoals, with touches of black chalk, stumping, erasing, incising, and subtractive sponge work, heightened with traces of white chalk, on cream wove paper altered to a golden tone, Art Institute of Chicago

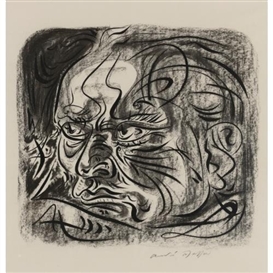

Redon continued to create, under mentorships of sorts from artists outside of the Academy, such as Camille Corot and Rodolphe Bresdin. The latter had a profound influence on Redon, as under him he learnt lithography, a process that the artist would go on to master. Redon’s artistic aspirations came to an abrupt halt in 1870, when he went to fight in the Franco-Prussian war. While the war may have interrupted Redon’s creative output, it had changed something within him, awakening a source of shadow-cast inspiration. Upon returning from the war he moved to Paris and began to create his now-revered “noirs” – lithographs and works rendered in charcoal, depicting the fantastical and the nightmarish.

Redon felt that humanity had lost its appreciation of what strange and eerie delights lay in the depths of the imagination, that they had grown blind to see what could not be seen. He implored for “a right that has been lost and which we must reconquer: the right to fantasy….” This philosophy made it somewhat difficult for Redon to appreciate such contemporary movements as impressionism, which was too grounded in the model for his liking. Although, interestingly enough, Redon would take part in the final impressionist exhibition, held in 1886. And while many may not have quite understood what Redon was trying to achieve with his work, his talent for working sans color was indisputable. Degas himself, even if he was somewhat puzzled by Redon’s subject matter, once expressed: “But his blacks! Oh! His blacks…impossible to pull any of equal beauty.”

Odilon Redon, The Abduction of Ganymède, c.1890-1900, oil on canvas, Foundation Bemberg, Toulouse

In 1880, Redon married Camille Falte, a young woman of creole origin. Camille would become a source of great stability for the introverted and fey artist. She would take charge of all dealings with dealers and printers, letting her husband focus on the act of creation. But despite the fact the Redon was completely and utterly immersed in his art, he struggled to bring sufficient money in from it. Even when the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans dedicated a lengthy mention of Redon’s work in his 1884 novel À rebours (Against Nature), the public still struggled to understand. It was not until after the artist had turned sixty, that he gained any sort of financial stability or more widespread artistic recognition. In 1903, he was awarded the rosette of the Légion d’Honneur, and the following year saw an entire room devoted to his work in Salon d’Automne. Two years later he was finally able to move his family into a better apartment. This change of fortune that seemed to coincide with the changing of the century in the most part stemmed from a shift in style. Gone was the almost-tangible darkness inherent in his charcoals. Instead it was replaced with colorful pastels and oils. This shift in style was largely due to Redon discovering Naturphilosophie – a German philosophy centered around the idea that everything in nature is interconnected, subsequently imbuing his work with celebratory color.

Odilon Redon, The Cyclops, c. 1914, oil on cardboard mounted on panel, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

At the onset of World War I, Redon’s son Arï was drafted. After not hearing any news of Arï for a worrying amount of time, Redon set out in terrible weather to a friend’s house in order to see if he had heard any word. The artist caught a chill in the process, and on July 6, 1916, succumbed to the great unknown. The tragedy was that Arï was very much alive, and would administer his father’s legacy until his own death in 1972.

Since Odilon Redon’s passing, his work has been accepted as being a pre-cursor to the surrealist movement. French surrealist André Masson praised Redon’s use of color alongside his chosen subject matter of the dream-like to exemplify this. Although, what is certainly strange about this point of view, is that Redon was creating works that were decidedly surrealistic during his “noir” period. One only has to gaze upon the Poe-inspired The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon, Mounts toward Infinity for a mere moment to be able to draw the parallels. But technicalities aside, Redon was held in very high regard by many of his contemporaries, and quite likely had significant influence on what was to come in the art world.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page