Blexbolex has cracked the code. The French cartoonist with the name that sounds like a friendly robot has worked in a wide variety of styles, from the simple interlocking blocks of bright color seen in his kid's books People and Seasons, to the whirls of limited-palette decoration in his very not-kid's books No Man's Land and Dogcrime. His most recent book, the truly all-ages fable Ballad, added a profusion of neon dot screening to the mix. Through it all, the constant is that his imagery bypasses people's critical faculties and hits them right in the pleasure centers, from page directly into eyes and usually from there to the wallet. Putting a Blexbolex book right by the tiller was a great way to grab add-on sales when I was working comics retail. He makes stuff that people want before they even know what it is, just because of how good it looks.

But overshadowed by his amazing artwork is his ability as a content creator. I hate that term too, but the word "writer" seems somewhat inaccurate as a description of Blexbolex's compositional role on People and Seasons; his more adult work is certainly written, and written well. While the dude isn't Alan Moore or anything, his stories that are actually stories have an admirable way of skirting expectations and surprising the reader by following unusual narrative pathways - even if those routes ultimately lead to destinations that might be less satisfying than those that more typically told stories provide. Blexbolex is such a skilled image maker that it'd be easy (and perhaps more lucrative) for him to only shoot layups and crank out conventional, corny pabulum for the kiddies' parents to throw money at, but he keeps on bombing three-pointers, and they go in more often than not.

My favorites of Blexbolex's works are actually his simplest ones, People and Seasons. These are children's picture books composed of full-page illustrations of weather phenomena and members of society, labeled with big, cheery typesetting. No story to them, really; they're more like visual dictionaries on specific topics. Like all their creator's work, they're gorgeous, but there's also a lot of fun to be had in seeing how iconic Blexbolex's pictures can get, how fully he's able to sum up "rain" or "firefighter" in one shot. So I was very pleased to see that his new book, Vacation, is another picture book from Enchanted Lion, the excellent Brooklyn publisher that issued those two. Bringing expectations to any Blexbolex book is a perilous proposition - and sure enough, Vacation is definitely not a catalog of "beach," "picnic," and so forth. It's a proper story, its author's first completely wordless outing, and it replaces the formal conceits and frequent oddness of Blexbolex's previous efforts with whimsy and charm.

If just seeing those two adjectives turns you off, this probably isn't going to be the book for you; but Blexbolex is still Blexbolex, and though this book has far more of a Pixarish crowd-pleasing element to it than anything else he's done, it still manages to avoid cliche and come away feeling fresh, far more than just a sentimental collection of pretty pictures. Vacation is the story of a girl, her grandpa, and the baby elephant who comes by train to join them at their countryside estate midway through the summer. The youths, both pachyderm and person, have trouble getting along; the grandpa does his level and somewhat ingenious best to patch things up; and things reach a satisfyingly ambiguous conclusion that neatly sidesteps the kind of cloying, saccharine ending everything in the story seems to be pointing to. There's not much more to the plot than that, but the plot doesn't matter too much in making an assessment of this book.

If just seeing those two adjectives turns you off, this probably isn't going to be the book for you; but Blexbolex is still Blexbolex, and though this book has far more of a Pixarish crowd-pleasing element to it than anything else he's done, it still manages to avoid cliche and come away feeling fresh, far more than just a sentimental collection of pretty pictures. Vacation is the story of a girl, her grandpa, and the baby elephant who comes by train to join them at their countryside estate midway through the summer. The youths, both pachyderm and person, have trouble getting along; the grandpa does his level and somewhat ingenious best to patch things up; and things reach a satisfyingly ambiguous conclusion that neatly sidesteps the kind of cloying, saccharine ending everything in the story seems to be pointing to. There's not much more to the plot than that, but the plot doesn't matter too much in making an assessment of this book.

Of far greater import are the pictures. As his career has gone on, Blexbolex's figures have become less iconic and more individualized; here, probably because he doesn't have any verbiage to lean on, they're more illustrative than ever, retaining their block printed simplicity while taking on a small dash of Miyazaki charm and specificity. They really emote, especially the little girl whose eyes we see the book's story through. Meanwhile, the Lichtenstein-esque dot screens used in Ballad are amped way up here, drenching every frame in sheets of moire'd, colorful fuzz. Sprinkles of complementary colors beat depth and dimension into basic shapes, and give the pictures' backgrounds a sense of endlessness. You can space out and enjoy peering into the light haze of crimsons and jades spreading over the vistas of dry, golden grass that the story's action takes place against and get just as much out of it as you would from doing more focused reading. The effect gives Blexbolex's usually pinpoint-sharp, hypermodern forms a faded, slightly crumpled air of nostalgia, the look of the colors in old newspaper comics or packaging labels.

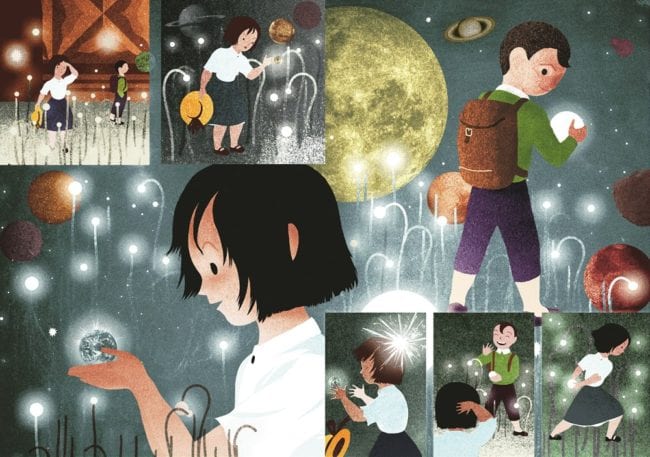

It's lovely, and it's also a signal: this book is playing to a grown-up readership just as much as it is to the elementary school crowd. Kids will certainly enjoy the trips to the cosmos and magic trains of the phantasmagorical dream sequences, but they're going to have to be pretty precocious to pick up on the heavy Winsor McCay influence Blexbolex is playing with. They'll be moved by the sadness of the little bullied elephant who just wants a playmate (as I certainly was), but grownup connoisseurs of graphic storytelling will be just as interested in the way multiple figure drawings of the same character are arranged in front of a single two-page master shot to track the patterns of kids at play. Blexbolex's previous comics work has been unconventional in looks, but never particularly so in formal style, usually simply adding captions to fixed, repeating panel layouts. Here, perhaps emboldened by going wordless, he wades fully into the space between traditional comics and picture books, using inset panels and sequenced imagery at times and letting full-page images stack up one after the next at others. The choices made are often audacious, but always feel appropriate, like the best way of putting forward what's being presented. Vacation really flows, and that's a hard thing for any wordless story to do.

It's lovely, and it's also a signal: this book is playing to a grown-up readership just as much as it is to the elementary school crowd. Kids will certainly enjoy the trips to the cosmos and magic trains of the phantasmagorical dream sequences, but they're going to have to be pretty precocious to pick up on the heavy Winsor McCay influence Blexbolex is playing with. They'll be moved by the sadness of the little bullied elephant who just wants a playmate (as I certainly was), but grownup connoisseurs of graphic storytelling will be just as interested in the way multiple figure drawings of the same character are arranged in front of a single two-page master shot to track the patterns of kids at play. Blexbolex's previous comics work has been unconventional in looks, but never particularly so in formal style, usually simply adding captions to fixed, repeating panel layouts. Here, perhaps emboldened by going wordless, he wades fully into the space between traditional comics and picture books, using inset panels and sequenced imagery at times and letting full-page images stack up one after the next at others. The choices made are often audacious, but always feel appropriate, like the best way of putting forward what's being presented. Vacation really flows, and that's a hard thing for any wordless story to do.

In fact, it flows so well that the abruptness of the final dream sequence's cut to the book's concluding scene caught me pretty off-guard. That's not a bad thing, as I'd been kind of dreading what I assumed was going to be a pat ending about learning to get along and be friends with people who are different from you. This is a book with rereadability, if only because it'll probably leave you scratching your head about what its final act means. Is the elephant a fairly not-ok metaphor for the African and Middle Eastern migrant kids who are slowly but surely becoming a part of European countrysides like the one this book takes place in? What, then, are we to make of the big festival sequence that kicks off the book's climax, where everybody dons animal masks? Or am I just going too deep with it when I should be putting more focus on those beautiful images? That's surely what the majority of this book's readership - the kids who'll pore over it again and again - will be doing. It speaks well of Blexbolex's talent as a guy who makes books, not just pictures, that his new one has more to it than meets the eye.

In fact, it flows so well that the abruptness of the final dream sequence's cut to the book's concluding scene caught me pretty off-guard. That's not a bad thing, as I'd been kind of dreading what I assumed was going to be a pat ending about learning to get along and be friends with people who are different from you. This is a book with rereadability, if only because it'll probably leave you scratching your head about what its final act means. Is the elephant a fairly not-ok metaphor for the African and Middle Eastern migrant kids who are slowly but surely becoming a part of European countrysides like the one this book takes place in? What, then, are we to make of the big festival sequence that kicks off the book's climax, where everybody dons animal masks? Or am I just going too deep with it when I should be putting more focus on those beautiful images? That's surely what the majority of this book's readership - the kids who'll pore over it again and again - will be doing. It speaks well of Blexbolex's talent as a guy who makes books, not just pictures, that his new one has more to it than meets the eye.