“I like the idea that the hand has a mind,” David Altmejd told me, as we walked through the new exhibition of his sculptures at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. That’s a very resonant comment when you see the recent work of this acclaimed Montreal artist, who now lives in New York. His pieces are full of hands cast from life, mostly disembodied, emerging in crablike procession from a figure’s hollowed chest, or clawing their way through flesh or the surface of a wall. They’re like verbs scuttling through his art, always making things or tearing them apart.

Some people, like me, may see these hands as visualizations of impersonal forces that we experience only as effects. We see a leaf wither, but not what drives that transformation. The work done by Altmejd’s sculptural hands, however, is often more surreal and macabre. In Le désert et la semence, a piece he completed three days before the show opened on June 20, two hands form a ball from sand and glue, which moves through a spiral of transformations from ball to coconut to skull to a man’s head, and from there to the head of a wolf, suspended high above the first stage of the process. A stream of sperm-like glue drips from the animal’s jaws to where the hands first gathered up the sand. It’s a complete cycle with no real beginning or end.

A nightmare, you might say, though Altmejd said he takes no direction from dreams, and is interested in surrealism and science fiction or fantasy only in that “they do offer a freedom to build and combine things.” More surprisingly, perhaps, he said that he sees the hands that gouge the surfaces of his angelic The Watchers and Bodybuilder statues as forces of self-transformation – the mind of the individual working on the self, not some outside power relentlessly tearing at the body.

The really striking thing about talking with Altmejd is how often he uses the language of freedom and transcendence to describe works whose material content can look fairly hellish. The Flux and the Puddle is a gigantic block of lucite boxes in which numerous figures are encased, throwing their transforming heads into space or standing with their guts or faces blown open and studded with mineral crystals. A pair of blackened humanoid figures slump over a table, mucking around with some dark, gooey substance that could become one of them. Mirrors inside and outside the block multiply its surfaces and magnify its contents, as teeth emerge from within pineapples, and streams of grapes and coconuts fly through the transparent structure like wind-borne projectiles.

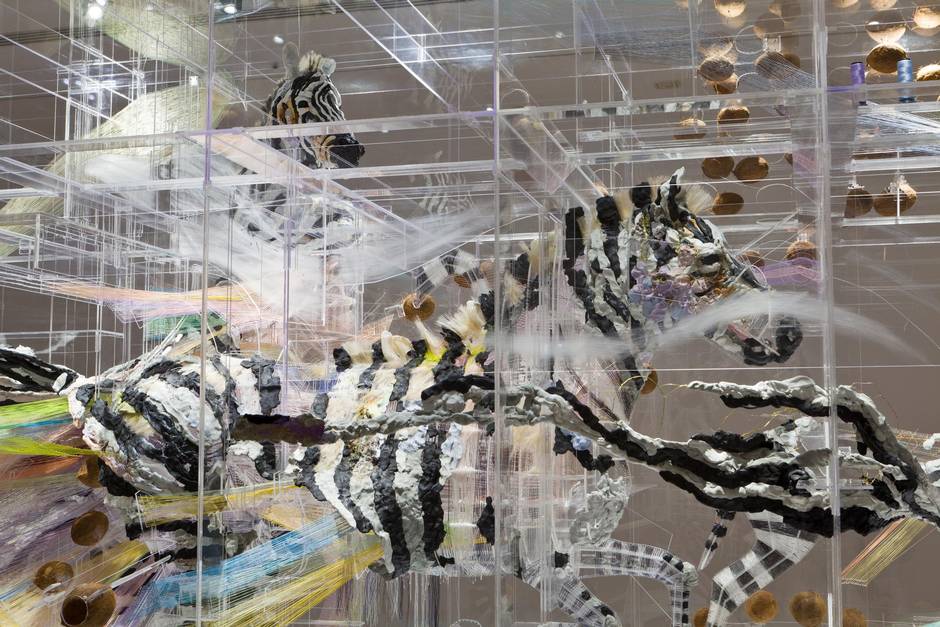

You could look at The Flux and the Puddle for a long time and still feel like you hadn’t seen the whole piece, which is part of the point. “I like the idea of an object that contains more volume than appears from its outside, an object that contains infinity,” says Altmejd. He’s also really into the illusion of weightlessness, as a way of liberating his material from its debt to gravity. In Le spectre et la main, another of his large lucite structures, a dense streaming network of coloured threads support two fragmentary zebras that float in space, their solid black and white stripes flowing away like weightless clay.

Altmejd studied biology before becoming an artist, and the relationship of his boxes with the vitrines of a natural-history museum seems obvious. But he’s not keen on that association, perhaps because his vitrines are really structural systems that are integral to the work, not just containers for things. Their many interior facets and the theatrical way in which they are lit, with spotlights from above, make them glow like large crystals that emit their own light.

All of these pieces are about drawing or painting in space with objects and coloured threads, and their feeling of movement and energy is impressive. You almost expect there to be a switch somewhere that might pitch the whole frozen process into action. But Altmejd’s streams of coconuts and grapes are also analytic representations of imaginary movements, akin to Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies. In that sense, Altmejd is both a stop-motion sculptor, and an animator who has no use for a camera.

Portraiture is a big element in this show, which includes a room full of heads, some of them with two sets of inverted features, others with crystals growing from holes and lesions – perfect structures growing from decaying ones. At the entrance to the exhibition stands a bust of the artist’s sister Sarah, the glinting face of which is hollowed out and blackened. These objects imply a drastic violence that in other parts of the exhibition shows up as holes smashed into mirrored surfaces, and – depending on how you look at them – those hands, ripping at flesh.

There’s also a gay erotic theme floating through Altmejd’s work, via the not-so-subtle coconuts, grapes, bananas and puddles of glue that persistently allude to male genitalia and semen. A full-sized sculpture of a bird-headed man in a suit includes a scrotum under the chin, apparently cast from life. The painstaking use of thread, however, which in the lucite pieces is strung through innumerable drilled holes, associates his art with the traditionally female world of needlecraft, and all the patient effort that implies.

Altmejd said that The Flux and the Puddle, which he completed in 2014, is the summation of a long period of work. “I wanted to include in it everything I had ever done as a sculptor,” he said. The next phase, he said, is represented by the single blackened figure that hangs upside down at the end of the exhibition’s last room. That’s another kind of space to explore, he said, and another kind of weightlessness. Whatever Altmejd finds there, it’s sure to be worth visiting with him.

David Altmejd: Flux originated at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la ville de Paris, and continues at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal through Sept. 13 (macm.org).