Giorgio da Castelfranco, otherwise known as Giorgione, is by general consent the most shadowy figure in the history of art. More is known about his death in Venice in the autumn of 1510 than his peculiarly elusive life. Nobody knows when he was born, when he left his native Castelfranco for Venice, whether it is true, as claimed, that he was a great musician and lover, only that he died of the plague in his early 30s. There is so little evidence of his brief passage through life, in fact, that some historians have wondered if he even existed.

Yet this short-lived and nearly mythical figure had such a colossal influence over Italian art – his name translates as the great George – that the early works of Titian, no less, would not look as they do without him. He is the poet of living minds and palpable thoughts, of inner dramas and outer beauty, of enigmatic figures in landscapes where the sun’s dying rays glimmer gold above distant blue towns, all painted with extraordinary softness and mystery.

His most famous work, The Tempest, shows a half-dressed woman suckling a baby in just such a landscape, surrounded by architectural fragments and observed by a soldier while lightning bolts flash in the sky. Nobody knows what the painting means, if indeed it has a meaning; whether it might be a narrative, an allegory, a pseudo-riddle without an answer or a scene painted purely for its atmosphere of fathomless mystery.

At least it is now agreed that The Tempest is by Giorgione. For his body of work is so disputed that some hardline historians believe there aren’t more than four certain paintings. His murals have faded, many of his canvases have disappeared and others, long thought to be by Giorgione, now seem to be the work of those who learned from him, such as Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano del Piombo and Titian.

How then, you might ask, can anyone ever hope to pluck a Giorgione show out of so much fog and confusion? The Royal Academy has pulled off something close to a miracle in this respect, not least because the curators have managed to borrow almost a dozen paintings by Giorgione from all around the world and many more by Titian and co. But beyond this feat, the show is superb, brilliantly presented with drama, sympathy, mounting surprises and the kind of deep scholarship that doesn’t just document art but actually loves it. It is in every respect exemplary.

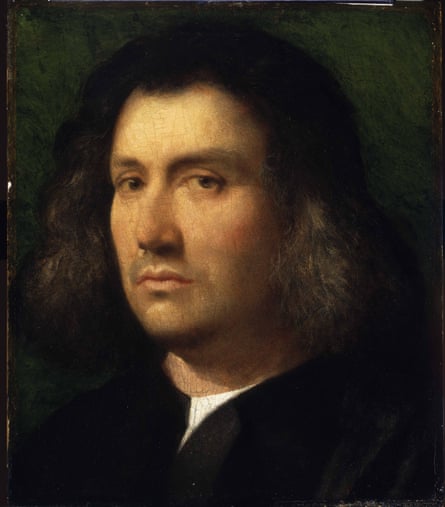

The show opens with Bellini’s portrait of a fair-haired gentleman in a black cap standing in front of a landscape of valleys and misty mountains. He is clearly an intellectual, one of his pupils slightly occluded to give a far-sighted gaze to the eyes. It is a painting of great immediacy – intimate, precise and crystal-clear – and anyone might stop there, compelled by Bellini’s serene lucidity. But hanging a few feet from it is a portrait of another gentleman, by Bellini’s sometime pupil Giorgione, that takes everything into the future. The head turns, the eyes continue the motion, sliding round to meet you, making an active event out of Bellini’s passive gaze.

The face is not a flat description but a marvellous three-dimensional portrait of a handsome Italian living in real time, muscles beneath the skin, five o’clock shadow, not merely the usual patch of grey paint but something emerging from within. His slightly saturnine look might evolve into humour, you feel, at any moment. Intensely dramatic, the portrait presents a man with an inner life that is beginning to surface in the public face as never before. It is like watching portraiture wake up.

The Terris Portrait, as it is known, has a period inscription on the back identifying Giorgione as the artist, though the sitter remains altogether more mysterious. But mystery is Giorgione’s exceptional gift. It is not just an atmosphere, carried in the beautiful smoky brushwork or even a question of narrative. It appears deep within the sitters themselves.

Why is this youth so depressed, head in hand, and holding an orange, while a perfectly cheerful sidekick crowds into the picture behind him? What is their relationship with each other, with life? Something says that this is a painting about love, but what strikes is the painful discrepancy between the two men and their moods. Is love a matter of temperament or luck?

The archer turns quickly towards us, as if his name had been called, or as if he were calling us to follow him. His face, with its parted lips and speaking eyes, is all open-ended suggestion, but his gloved hand touches the gleaming breastplate with a declaratory gesture – myself, here, now – repeated in the exquisitely painted reflection. Whoever he is, this boy is far more than an archer.

The show is perfectly choreographed to flow from single heads in the first gallery to half-length portraits in the second. Hands come into play, leafing through books, strumming guitars, resting on polished helmets or stone ledges. Bodies incline forwards or backwards, turn this way and that. Solo portraits become doubles as second figures arrive to complicate the narrative.

The sense of animation builds as people turn and point, urging us onwards, and eventually appearing outdoors into those seductive landscapes. Everything is coming alive. A stunningly charismatic portrait of a young poet, eyes lowered, hand on heart, as if to contain all the sorrow inside him, prefigures Romanticism by about four centuries. And all of this is happening in not much more than 10 years of Giorgione’s life in Venice.

There is a double fascination to this show in that it attempts to capture Giorgione in both the positive and the negative – what he was, but also what he was not. Even the curators don’t agree on which paintings are by Giorgione and which by the young Titian, for instance, and they have positioned the Terris Portrait at the start as a kind of Rosetta Stone for everything that follows.

They are also very candid about fictions (Giorgione became so popular in the 19th century that thousands of paintings were said to be by him). Il Tramonto, for instance, is an extremely strange landscape with an old man tending to the leg of a young man, made all the stranger by addition of a boar, a hermit and St George lancing his dragon in the 1930s. Patches of the painting were lost; a dealer had them filled in and invented a title to echo La Tempesta.

But Giorgione is still visible behind all this and your eyes are now sufficiently attuned to see him. That is one of the show’s gifts: it invites the viewer to look at many paintings made in the same place at around the same time and recognise Giorgione’s outstanding originality. For that is surely the telling trait. Here was a man who painted himself as David holding the severed head of Goliath that inspired Caravaggio a century later. Here was a man who could paint the most beguiling of all puzzle paintings and produce the portrait that deservedly appears as the climax of this show: of a most vivacious old lady. Her hair is greying, her cheeks wrinkled, the hand at her breast is supposedly saying I am old, as you will one day be, too. Or at least that is the warning written on the slip of paper tucked in her cuff: “With time”. But look at her profoundly subtle face, in all its charm and intelligence, and the message (surely another late addition) is undermined. This is not the kind of allegory of age everyone else was painting but a portrait of a real woman, endearing, humorous, with the light of experience bright in her eye.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion