To some, Harlan Ellison was the finest short story writer to have emerged from America’s science fiction ghetto in generations. The Los Angeles Times described him as “the 20th-century Lewis Carroll”; JG Ballard thought he was “an aggressive and restless extrovert who conducts life at a shout and his fiction at a scream”; Robert Bloch, author of Psycho, called him “the only living organism I know whose natural habitat is hot water”.

Ellison, who has died aged 84, wrote 70 books, some 400 short stories, dozens of TV screenplays and more than 1,000 essays, introductions and columns. His stories could be whimsical and cruel, playful and painful, sentimental and shocking. He loathed being branded a “science fiction” author, although a tally of more than 40 awards proved that SF fans held him in high regard. He was given lifetime achievement prizes by the World Fantasy awards and the Horror Writers Association, and received the Writers Guild of America award four times. In 1996 he said: “What I write is hyperactive magic realism. I take the received world and I reflect it back through the lens of fantasy, turned slightly so you get a different portrait.”

Ellison was anti-Vietnam, an advocate of gun control and a supporter of human rights organisations. His social concerns were reflected in stories such as “Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman (1965), about civil disobedience in a world of rigid conformity, which won the Hugo and Nebula awards. He also received Hugos for I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (1967) and for The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (1968). Ellison’s development as a writer coincided with the growth of SF’s new wave, championed by Michael Moorcock, Ballard and Brian Aldiss in the British magazine New Worlds. Ellison invited dozens of authors on the cutting edge of the new wave to contribute to the anthologies Dangerous Visions (1968) and Again, Dangerous Visions (1972). His screenwriting credits included a notable episode of Star Trek, entitled The City on the Edge of Forever, which was a bone of contention on numerous occasions, from spats between Ellison and the show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, to Ellison’s 2009 lawsuit against Paramount/CBS for unpaid royalties from the merchandising of the episode. After he claimed that James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) bore similarities to his own work, later prints of the film included an “acknowledgment to the works of Harlan Ellison”.

Although for many years Ellison was dismissive of computers, he later embraced the power of the internet, publishing books and ebooks through his own website. Never shy of publicity, he performed a number of stunts over the years, including writing a story a day while sitting in the windows of bookstores in Los Angeles, Boston and Charing Cross Road in London, and writing in a hotel lobby during a convention, and even writing live on radio. He was the subject of a documentary, Dreams With Sharp Teeth (2008), and “played” himself in episodes of Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated and The Simpsons.

He was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the son of Louis and his wife, Serita (nee Rosenthal). Louis, a former singer, worked as a dentist and then at his brother-in-law’s jewellery store in Painesville, Ohio, where Harlan went to school. His only achievement at school, he said, was a national award for a story he “shamelessly pilfered” from Karel Čapek’s play RUR. He was well-read, citing Joseph Conrad and Immanuel Kant as his boyhood favourites. James Otis Kaler’s children’s novel Toby Tyler: Or, Ten Weeks With a Circus inspired him to run away, aged 13, to join a travelling funfair. He ended up spending three days in a cell in Kansas City, refusing to give his name. Comic books and pulp magazines were a more discernible influence on his earliest stories, written and illustrated for the children’s column of the Cleveland News.

In 1949 Ellison’s father died and he moved with his mother to a residential hotel in Cleveland, where his interest in science fiction pulps led him to co-found a local fan group. He was the editor and principal writer for the Bulletin of the Cleveland Science Fiction Society, which morphed into Ellison’s own fanzine, Science Fantasy Bulletin (later Dimensions). In 1953 he entered Ohio State University but was thrown out following an incident when he verbally abused a professor of creative writing who had been dismissive of his talent.

Having sold a script to EC Comics, and now determined to write full-time, he moved into an apartment with the SF writer Robert Silverberg and collected rejection slips, earning a living by selling pornographic books in Times Square. Inspired by popular novels of gang life, Ellison (as Phil “Cheech” Beldone) joined a Brooklyn gang, the Barons, for 10 weeks and sold an article about the experience to Lowdown magazine. It was completely rewritten and Ellison’s photograph was printed with the addition of a drawn-in scar on his left cheek.

His first published short story, Glowworm, appeared in the American science fiction magazine Infinity in 1956, and over the next few months Ellison sold with increasing regularity to magazines. Also in 1956 he married Charlotte Stein, although he later described their relationship as “four years of hell as sustained as the whine of a generator”.

Drafted into the army in 1957, he trained at Fort Benning, Georgia, and was posted to the Public Information Office at Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he filled the pages of the weekly newspaper with articles and reviews. His first novel, Rumble, and short story collection, The Deadly Streets, both appeared in 1958, although Ellison’s huge output of up to 10 published stories a month shrank dramatically as he decided it was time to write the stories he wanted to, rather than those he had to write to support himself.

Released from the army, Ellison took up the invitation of the Illinois-based publisher William Hamling to become editor of the men’s magazine Rogue. He hired Lenny Bruce and Alfred Bester as columnists and gave the paper an identity that could have rivalled Playboy. However, following his divorce Ellison entered a self-destructive cycle of partying and womanising, and, after falling out with Hamling, was persuaded by the SF author Frank M Robinson to leave Rogue and take up writing full-time again. As a result, he wrote Spider Kiss (1961), the story of a monstrous rock’n’roll singer based on Jerry Lee Lewis.

Ellison married Billie Sanders in 1960 and accepted an editorial job from Hamling on the Nightstand range of sex novels, on condition that Hamling also publish a line of mainstream books to be chosen by Ellison. The Regency Books imprint published Ellison’s collection Gentleman Junkie and Memos from Purgatory, which combined his “Cheech” Beldone memoir with the story of how he came to spend a night in New York’s infamous jail, the Tombs.

Realising he had made a mistake in returning to work for Hamling, Ellison escaped back to New York, sold another collection (Ellison Wonderland) and then moved to the west coast with his wife. They divorced in 1962. A review of Gentleman Junkie by Dorothy Parker in Esquire described Ellison as “a good, clean, honest writer, putting down what he has seen and known, and no sensationalism about it”. It turned his career around.

Arriving in Los Angeles in 1962, Ellison found work writing for various TV series, including Ripcord, Burke’s Law, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Outer Limits, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. His movie-writing career was less successful. He co-wrote the critically savaged The Oscar (1966) and in 1975 an adaptation of his own A Boy and His Dog, directed by LQ Jones. Set in a post-apocalyptic world, it starred Don Johnson as a survivor seeking food and sex with the aid of his telepathic dog, Blood.

Ellison’s TV credits tailed off in the late 60s as his fiction gained more widespread approval, although he created The Starlost, a science fiction series produced in Canada. Ellison’s original pilot script was revised by other hands, becoming a travesty from which Ellison had his name removed. Not for the first time, he insisted that the moniker “Cordwainer Bird” be substituted. He became involved in the revival of The Twilight Zone, but quit when one of his scripts was censored. He was also a creative consultant for Babylon 5.

His output over the years was littered with projects that fell by the wayside. An ambitious 20-volume library of Ellison’s work was begun by White Wolf in 1996 but collapsed after only four volumes a year later. Ellison created The Kilimanjaro Corporation in 1979 to handle all his works and copyrights. From 2011 he self-published a number of titles on his website.

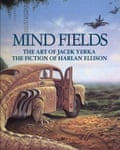

In 2000, he had begun producing a weekly series of commentaries for Galaxy Online under the title Working Without a Net, also the title for his proposed memoirs, sold in 2008. Of all his books, he claimed that he was most proud of Mind Fields (1994), a collection of 33 stories each based on a painting by the Polish surrealist Jacek Yerka.

In 2010, in poor health, he announced that his guest of honour stint at MadCon in Madison, Wisconsin, would be his final convention appearance. The following year he was diagnosed with clinical depression and put on a spectrum of medicines.

Ellison married Lory Patrick in 1966 (they were divorced within a few months); Lori Horwitz in 1976 (divorced in 1977); and Susan Toth in 1986. She survives him, along with his niece, Lisa, and nephew, Loren.

Harlan Jay Ellison, writer, born 27 May 1934; died 27 June 2018

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion