In 1986 I was commissioned by the recently set up Channel 4 to direct two hour-long documentaries about the Hollywood-based production company BBS. This was set up by legendary producer, Bert Schneider, director Bob Rafelson and accountant Steve Blauner. They blew a giant hole in the studio-based Hollywood system by making movies for under $1m.

Their best-known productions were The Last Picture Show, Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens. Dennis had come upon BBS in the late 1960s via Peter Bogdanovich, who had made a terrific thriller, Targets, about a pathological gunman who killed, without motive, the drivers of cars on motorways.

This was financed by Roger Corman who wanted to back Easy Rider until his bankers sat down for a meeting with Dennis, the putative director of the project, whose language by all accounts was so colourful they refused to countenance him as helmsman. So Dennis upped and went to Bert Schneider, who agreed to produce it, and the rest as they say is history.

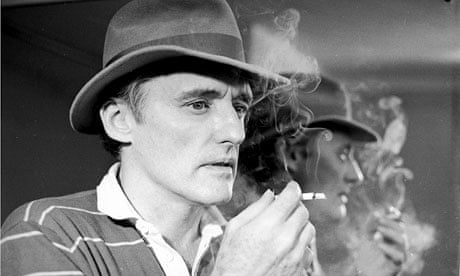

From the very beginning, Dennis had his moments. After a terrific start in 1955 with Rebel Without A Cause and a soul-changing meeting with James Dean, it underwent a juddering halt when he tried to mess with Hollywood veteran Henry Hathaway. He was cast in a minor role in From Hell to Texas and found it impossible to take the intricate direction Hathaway was determined to give him. Over the course of a day and a night and over 80 takes, he was interrupted by studio executives calling Dennis, “Hey kid, this is Hathaway you are fucking with, do you want to work again or not?”

Dennis was reduced to a catatonic lump of weeping jelly. Banned from every set in Hollywood, he told me he planned a million and one ways to dispose of Hathaway, but decided to wait, see and hope.

A decade later and Dennis was probably all but uncontrollable. While Easy Rider was being produced he was sitting next to the veteran director George Cukor at a Hollywood dinner and suddenly turned to him, saying: “you are old Hollywood and we’re the new. We are going to BURY YOU”. Not quite the way to behave even in impolite society, and the way Easy Rider was actually made and finally completed is a tremendous tribute to Bert Schneider’s ability to hold a rein on a disintegrating project.

And filming was only part of the story – after editing it for a year, Hopper wanted to show a full five-hour version without further cuts. So a team of editors began to trim the film, working from both ends and arriving, finally, at some agreed mid-point. Then, even when it won best first film at Cannes, US executives did not see the potential of the film until word-of-mouth gathered together the 1960s generation who absolutely understood the philosophy expounded by Hopper, Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson and filled the aisles (all other seats being taken) of cinemas worldwide.

Anyway, back to 1986 and we arrive with a full film crew (yes, in those days we even travelled with one) in LA to interview Dennis, only to find that he is in hospital with a suspected overdose and basically “out of it”. Again, it is Schneider who visits Dennis, calms him and re-motivates him. So we hang about the Chateau Marmont hotel and wait for Dennis to recover, filling our time with key interviews from other BBS players. One of these is Ned Tanen, a Hollywood executive apparently carved out of granite who ran major studios all his life and had the misfortune to inherit Dennis’s next project: 1971’s The Last Movie.

Well, he told us, it very nearly was. Shot in Taos, New Mexico, where Dennis had tried to introduce the natives to the French “New Wave” at the local flea-pit without a great deal of success (there were many variegated stains on the screen as a result) this rambling stream-of-consciousness movie almost brought Dennis’s career to a much earlier close.

He replaced the actor chosen for the lead, Ben Johnson, with himself and proceeded to embark on a series of existential adventures which left even the nouvelle vague well behind. Poor Tanen, beholden to his shareholders and board members, who all dumped on him from a great height, could only muster the following comment about Dennis even long after the event: “He is, I think, some kind of genius…”

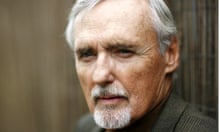

The public reaction to the death of such an icon will be fascinating to observe. So far people seem to be mentioning Easy Rider, almost as a matter of course, and his role as the multiple-substance-addicted heavy in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. Famously he told Lynch that he was not going to play the part: he was the part.

This reminds me of Dennis’s comment about talking to James Dean, when they were really no more than students, and Dean said to him: “Don’t act drinking from the glass just drink!” Essentially this note from friend to friend saw Dennis through five decades of memorable appearances on large and small screens.

There was so much more to him than this, though. Dennis’s work as an artist and photographer has, in my opinion at least, been overlooked disgracefully in the UK. It was to be the Hermitage in St Petersburg that offered Dennis, two years ago, a one-man show – something unheard of even for a Soviet artist. His pride in this aspect of his work was deeply felt, but privately held, attended to and enjoyed.

My abiding memory of him is someone who always saw the humour, even in the blackest of moments. He was also a fantastic friend.

It was Dennis’s great regret that he only achieved eight credits as a director (against over 200 as an actor) and he felt that those talents were badly neglected. This is my opinion too, but in a sense his mischievous screen persona, used to such advantage in the films of others, became a millstone and sapped his time and energy.

Inevitably the question on this so sad day is: how will history remember him? Well, he lived long enough for the hell-raising days of his youth to be forgotten, or not even to be recognised by younger generations of filmgoers. This alien from the Sixties, unrecognisable through the whiskers and long hair, riding forever through both real and imagined deserts: it is he, Dennis, who carries with him our hopes and dreams. What did he amount to? What did he achieve? A handful of great acting performances, some wonderful films as a director, three or four incredible art collections dissembled by ungrateful wives, many loyal and devoted friends and the respect of his luckier colleagues.

Perhaps the ultimate irony is that he was embraced by the very Hollywood establishment he was determined to bury, and it is now they who will be burying him.

Paul Joyce is a documentary film-maker and artist

His best films

Rebel Without a Cause

(Nicholas Ray, 1955)

His fresh-faced 1955 debut, insecure and in the shadow of James Dean, whose spirit he so determinedly carried on.

Easy Rider

(Dennis Hopper, 1969)

His first film as director was a complacently subversive countercultural movie that made him a fortune and turned his friend Jack Nicholson into a star. His collaborator was black humorist Terry Southern, co-writer of Dr Strangelove.

The Last Movie

(Dennis Hopper, 1971)

A truly wild western, perhaps the greatest expression of the 1960s zeitgeist. Its producer, Universal Studios, buried it for a decade after it received critical acclaim at Venice.

Tracks

(Henry Jaglom, 1976)

One of the best, most rarely revived Vietnam movies in which Hopper’s veteran brings the war back home.

The American Friend

(Wim Wenders, 1971)

Hopper involves himself in the new European cinema as Patricia Highsmith’s psychopathic Tom Ripley.

Hoosiers

(David Anspaugh, 1986)

Hopper gives his greatest performance as an alcoholic former high school basketball star seeking redemption.

Blue Velvet

(David Lynch, 1986)

In his later career, Hopper turned in a succession of truly terrifying heavies, of which the menacing small-town gangster Frank Booth (a role he begged for) is the most nightmarishly unforgettable.

Selected by Philip French