It is one of the great causes célèbres of the cold war. At around noon on 29 October 1965, Mehdi ben Barka, a Moroccan opposition leader and hero of the international left, was abducted as he arrived at a brasserie on Paris’s left bank.

Over the years, much of the truth about the murder of the 46-year-old dissident has emerged: how he was taken to a house south of Paris, tortured and killed by Moroccan intelligence agents. But many of Ben Barka’s activities before his death have remained shrouded in mystery. Now new research in the archives of former Soviet satellite states has revealed that the charismatic intellectual, propagandist and political organiser may also have been a spy.

Previously classified files from Prague show that Ben Barka not only had a close relationship with the Státní Bezpečnost (StB), the feared Czechoslovak security service, but that he received substantial payments from it, both in cash and in kind.

“Ben Barka is often depicted as a fighter against colonial interests and for the third world, but the documents reveal a very different picture: a man who was playing many sides, who knew a lot and knew too that information was very valuable in the cold war; an opportunist who was playing a very dangerous game,” said Dr Jan Koura, an assistant professor at Charles University in Prague, who gained access to the file.

The findings will be controversial. Ben Barka is still a hero for many on the left, and his family adamantly deny any accusations that he was involved in espionage or had close ties with any state.

A possibility of a link between Ben Barka and the StB was first raised almost 15 years ago, though few paid much attention to investigations by a Czech journalist. But Koura was not only able to access the entire Ben Barka file in the StB archives but cross-check its 1,500 pages with thousands of other newly released secret documents.

“There is no doubt about [the Czech connection]. All the documents confirm it,” Koura told the Observer.

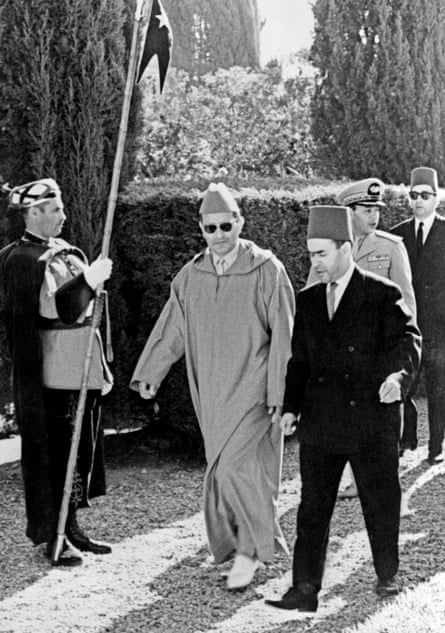

According to the file consulted by Koura, Ben Barka’s relationship with the StB began in 1960, when he met its most senior spy in Paris after leaving Morocco to escape the increasingly authoritarian rule of King Mohammed V. His homeland, a former French colony, had been pro-western since the beginning of the cold war but had recently tilted closer to Moscow. Prague’s spies hoped this prominent leader of Morocco’s fight for independence and founder of its first socialist opposition party would provide valuable intelligence, not just about political developments in the kingdom but also about the thinking of Arab leaders such as Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Ben Barka was also a major figure in the “anti-imperialist movement of African and Asian nations”, the StB noted, whose contacts included Malcolm X, Che Guevara and the young Nelson Mandela. Soon after their first meetings, the StB was reporting that Ben Barka was a source of “extremely valuable” information and gave him the codename “Sheikh”, the archives reveal.

By September 1961, according to the file, Ben Barka had received 1,000 French francs from the StB for reports about Morocco that he claimed were copied from the internal bulletin of France’s overseas intelligence service. In fact, the material was publicly available, which led to anger and embarrassment in Prague when the deception was discovered. Ben Barka was nonetheless then offered an all-expenses-paid trip to west Africa to gather intelligence on US activities in Equatorial Guinea. This mission was considered a success.

The Czechoslovaks soon began to suspect that Ben Barka had relationships with other cold war players too, hearing in February 1962 from an operative in France that “Sheikh” had met an American trade unionist at L’Éléphant Blanc bar in Paris and received a cheque made out in US dollars. This led to concerns that Ben Barka had connections to the CIA, which was keen to support democratic reform in Morocco and secure the kingdom for the western camp. The StB was to receive further reports alleging Ben Barka was in contact with the US, though the Moroccan politician always denied this when confronted, Koura said.

The relationship continued nonetheless. The Czechoslovaks invited Ben Barka to Prague, where he agreed to help influence politics and leaders in Africa in return for £1,500 a year.

Ben Barka was despatched to Iraq to obtain information on the coup of February 1963, for which he received £250, according to the documents. In Algeria, he repeatedly met Ahmed ben Bella, the president and a friend, and reported on the situation in the newly independent state.

In Cairo, he was asked to gather information from senior Egyptian officials that could help the Soviets in negotiations during a visit by Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier. Ben Barka’s reports reached Soviet intelligence services, which judged the material provided as “highly valuable”. As a reward for his services, he and his four children were invited on holiday to a spa in Czechoslovakia, Koura’s research reveals.

“Ben Barka never admitted that he was collaborating [with intelligence services], and the StB never listed him as an agent, just as a “confidential contact”. But he was providing information, and was paid,” Koura said.

“He was very clever, a very smart guy. There is no document with his signature, there are no samples of his writing. He was questioned orally for hours ... Occasionally, he used a typewriter but refused to write anything by hand.”

The motives of Ben Barka, a committed activist who was arrested and imprisoned repeatedly in Morocco, remain unclear.

His defenders say he was willing to repeatedly discuss the international situation with Czechoslovak officials as this was the best way to influence them. They also say that although Ben Barka’s analyses may have been useful to the StB, this does not make him “an agent”, whatever was written by ambitious bureaucrats and spies on internal memos.

They argue too that such a role would have been incompatible with Ben Barka’s dedication to preserving “the third world movement from both Soviet and Chinese influence”.

Bachir ben Barka, who lives in eastern France, told the Observer that his father’s relationships with socialist and other states were simply those to be expected of anyone deeply engaged in the global struggle against imperialism and colonial exploitation at the time, pointing out that the documents studied by Koura had been “produced by an intelligence service, [and so were] perhaps edited or incomplete”.

Koura is less convinced of Ben Barka’s altruism. “There was both pragmatism and idealism. I don’t condemn him. The cold war was not just black and white,” he said.

In his final months, Ben Barka was busy organising the Tricontinental Conference, an event that would bring together in Cuba dozens of liberation movements, revolutionary groups and their sponsors. The conference would become a crucial moment in the history of international anti-colonialism in the 1960s and 1970s, and the veteran activist wanted to chair the event.

But the Soviets suspected he had become too close to the Chinese, their rivals for leadership of the global left. Soviet officials told the StB that Ben Barka had received $10,000 from Beijing, and pressured the service to withdraw any support or protection for him.

Nonetheless, the StB brought Ben Barka to Prague for a week’s training in communications, codes, surveillance and counter-surveillance. This was too little, too late, however. A week after requesting a handgun from the StB, Ben Barka was abducted and killed.

Though he ordered an investigation, President Charles de Gaulle denied any involvement of the French secret services and the police. France and the US have yet to release key secret documents on the case.

Prague tried to blame the apparent assassination of Ben Barka on the CIA, the new Czechoslovak documents reveal. This fooled few. In a document obtained by the Observer under British Freedom of Information laws, London’s diplomats praise the “moderation” shown by Paris in the face of “overwhelming” evidence that Morocco’s intelligence services were responsible.