What I Didn’t Expect from the Spanish Inquisition

As I began researching South of Sepharad, I went into my understanding of what occurred during the Spanish Inquisition with many preconceived notions. I assumed the Inquisition was a medieval genocide, an overwhelming carnival of the macabre inflicted on Jews and Muslims by religious heretics; that people were burned at the stake and their bodies mutilated on the rack for the slightest offense.

However, the more I learned about the Spanish Inquisition, the more I began to realize that my original impressions–likely taken from movies and TV–were largely an exaggeration of what happened. The Spanish Inquisition itself is far more complex than I thought.

Before the Inquisition

Despite its infamous reputation in world history today, Spain actually came late to the practice of medieval European countries persecuting their Jews. Jews were banished from France in 1182, then England in 1290. Due to the presence of Muslims on the Iberian Peninsula for approximately eight centuries, Spain was more ethnically and religiously diverse than its northern neighbors. This cohabitation of Muslims, Christians, and Jews meant a greater tolerance for other religions.

This is not to say that riots and violence were never committed against Jews in pre-Inquisition Spain–there were many instances where Jews were forced to convert to Christianity or be put to death. However, these instances were isolated and not endorsed by the crown or Vatican.

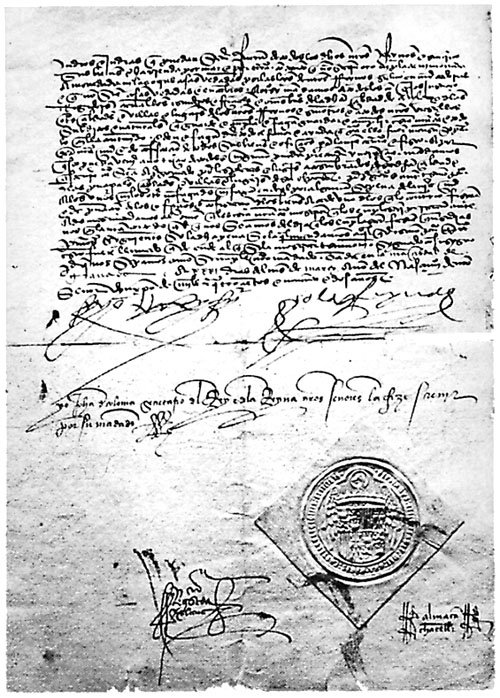

But everything changed when Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon (known together as the Catholic Monarchs) rose to power and requested that Pope Sixtus IV permit them to combat heresy in their kingdoms. On November 1, 1478, the pope issued a decree that would allow them to begin their work and the Spanish Inquisition was born.

Historians differ on what exactly motivated the Inquisition. The simple answer is that–on the verge of conquering all Muslim Spain–the Catholic Monarchs wanted to combat heresy. They wanted to shape their new kingdom into a Christian empire and ensure that no Jews and Muslims could intervene. In 1492, they issued the Alhambra Decree, requiring all Jews to convert or leave Spain forever.

The Inquisition

By the time the Alhambra Decree went into effect, Jews who wished to remain on Spanish shores converted to Christianity. Although their agreement to convert should have allowed them to live in peace as conversos (as they were called), the Inquisition continued to hold strong suspicions that many people who converted falsely were practicing old beliefs in secret. These suspicions extended to Muslims as well, who were forced to convert in the early 1500s.

To flush out the heretics, the Inquisition would arrive in cities throughout Spain and issue an Edict of Grace, a 30–40-day window where locals could confess to heresy and receive less severe punishments thanks to their transparency. Locals would confess to anything, as it was better to brand yourself as a heretic for a minor offense during this window than wait for someone else to accuse you.

Inquisitors then ordered these confessors to name other heretics as part of their penitence. This was where things really got out of hand, as neighbor accused neighbor, friend accused friend, and family member accused family member, all to stay on the good side of the Inquisition.

The Accused

Before beginning my research, I had assumed that if you were accused of heresy by the Inquisition, you were given a quick show trial before being whisked off to the stake. However, the actual process was much lengthier and more bureaucratic.

If you were accused, the Inquisition would show up at your home unannounced and bring you to be judged by a tribunal known as the High Tribunal of the Holy Office. The Inquisition would force you to wear a monk’s habit and shackles. Once before the tribunal, you’d be accused of heresy. You would not know who had brought these accusations against you nor what you’d done to warrant such an accusation.

With your life on the line, you had a few options:

If you wanted to survive, you would need to provide voluntary reconciliation. You’d beg for forgiveness and assure the tribunal you’d be a good Christian from here on out. Or: you would undergo forced reconciliation. You’d be tortured until you repented and vowed to be a good Christian moving forward.

If you reconciled quickly enough, you’d be allowed to live, but in great shame. People would avoid you in the streets, only acknowledging you if it meant throwing trash at you (such as eggshells and old fruit). Whenever you went out, you’d be forced to wear a sanbenito: an article of clothing that marked you as a sinner and forever showed people your shame.

The Inquisition would only put you to death if you refused to repent. You would be locked up, tortured, and brought before the tribunal many times – all to make you accept Christianity. If you refused, you would be imprisoned until the next round of public executions, which occurred every few months.

“The Inquisition Tribunal” painted by Francisco de Goya between 1812-1819. The dunce cap-like headpiece atop the condemned is a sanbenito. Source: Wikipedia

The Execution

A public execution of this type was known euphemistically as an Act of Faith (auto-da-fé). The morning of the execution, you would be shackled to your fellow condemned and marched into the town square. After several sermons performed by the church, you would be given one last chance to repent before being turned over to the authorities for execution.

In paintings and medieval torture museums dedicated to the history of the Inquisition, I’ve seen people be killed any number of ways: quartering, beheading, flaying, etc. However, I cannot verify how common these methods were. In most you would meet death in one of two ways:

If you repented at the last minute, you’d be strangled to death before having your body burned (this was deemed the more attractive option). However, if you refused to repent until the very end, you would be burnt alive at the stake.

After your death, the Inquisition would send your family the bill for your imprisonment, torture, and execution.

“Auto de fe en la plaza Mayor de Madrid” by Francisco Rizi. The painting portrays the celebration of an auto-da-fé in Madrid’s Plaza Mayor, presided over by King Carlos II on June 30, 1680. Source: Wikipedia

The Legacy of the Inquisition

Understanding the full pipeline of going through the Inquisition helped me realize that too much bureaucracy was involved for the Inquisition to mass murder people on a regular basis. This is not to say that Inquisitors were not severe in their methods of torture and execution from time to time–indeed, one of the characters in South of Sepharad is put before an especially radical tribunal that occurred in the early days of the Inquisition. However, I do not believe that killing people on a whim was ever the official policy or practice of the Inquisition.

In addition, historians differ wildly on how many people they believe were put to death during the Inquisition. I’ve read numbers as low as 2,000 and as high as 32,000.

What is true about the Inquisition is that it spawned fear and paranoia within Spain for centuries, brought those same practices to the Spanish colonies in the Americas, and isolated Spain from the rest of Europe for over 300 years.

The Spanish Inquisition was not officially abolished until July 15, 1834.

Sources:

Spanish Inquisition Key Facts

Inquisition

Ugly History: The Spanish Inquisition

Against the Inquisition

Granada: Pomegranate in the Hand of God

A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, Vol. 2

About the Author

Eric Z. Weintraub earned an MFA in Creative Writing from Mount St. Mary’s University where he wrote his debut novel South of Sepharad. Growing up in Los Angeles, CA, he came from a family of filmmakers, writers, and educators stirring in him a passion for storytelling from a young age. His short fiction has appeared in Tabula Rasa Review, Halfway Down the Stairs, The Rush, and elsewhere. His novella Dreams of an American Exile won the 2015 Plaza Literary Prize and was published by Black Hill Press. His short story collection The 28th Parallel was a finalist for the 2021 Flannery O’Connor Award in Short Fiction. When not writing fiction, Eric profiles true stories of complex medical cases where he works at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.